East Asia Blog Series

Eliminating Plastics in the Era of Food Delivery: The PRC’s Solutions on Reduce, Reuse, and Substitute

Hsiao Chink Tang and Xiaowei Zhuang 8 Dec 2021

Ten years ago, online food delivery services barely existed in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In 2020, it grew to become a $51.5 billion industry representing half of the global market share. The PRC is not alone. The Southeast Asian market tripled in 2020 accelerated by the coronavirus pandemic.

Although the booming industry has powered economic activity and brought unparalleled convenience to hundreds of millions of consumers, it has also generated a significant amount of waste that litters cities, chokes rivers, and threatens wildlife.

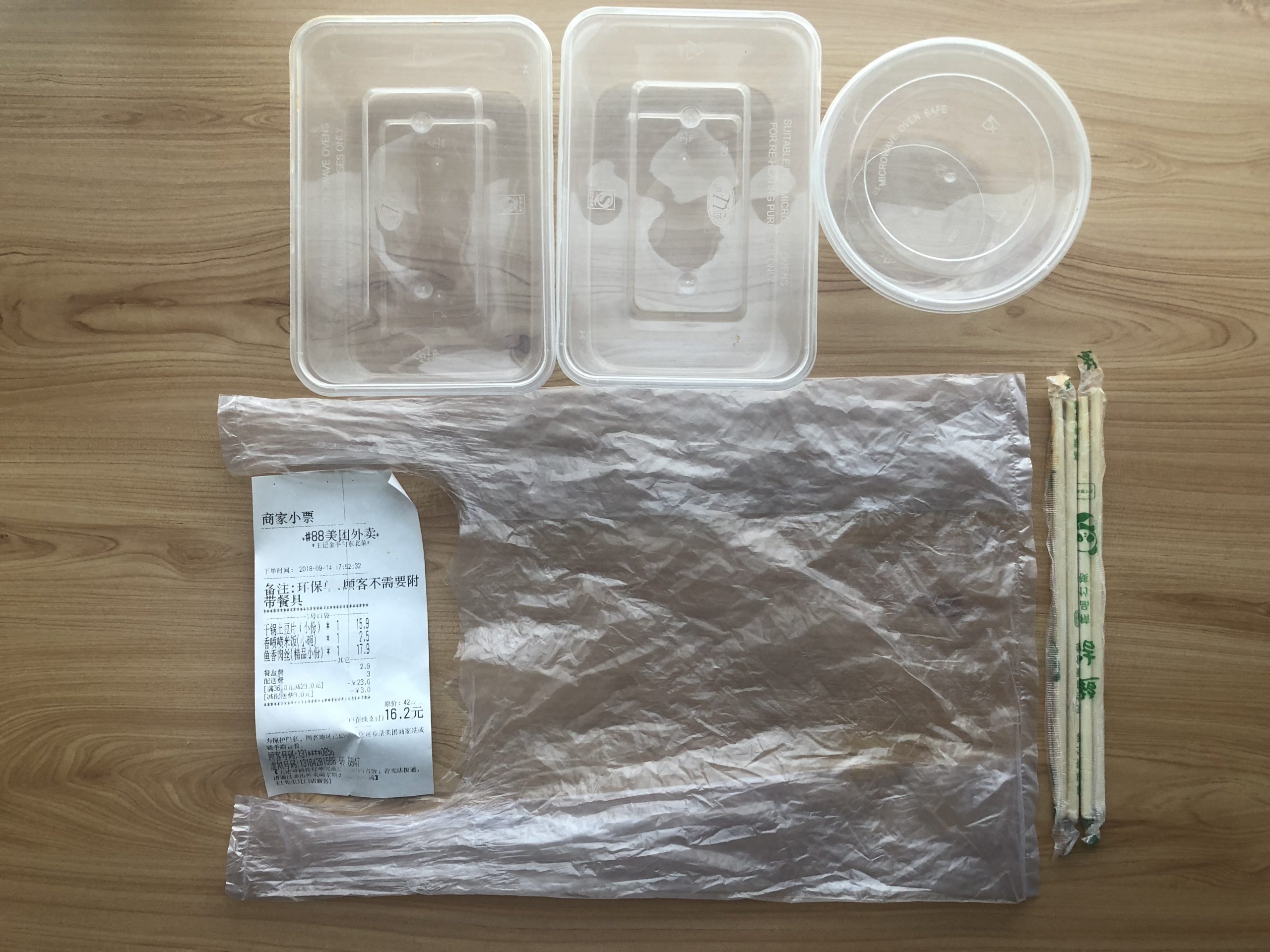

Figure 1: Ecosystem Services of Nature-Based Solutions.

In the PRC, we estimated that 37 billion plastic containers were discarded in 2020, based on the 17.12 billion online food orders made. 1 If we were to line up each piece, this would be equivalent to about 37 times the distance between north to south pole. As disturbingly, the containers take centuries to biodegrade, but about an hour to use.

In response, companies in the PRC have adopted innovative ways to combat environmental and health issues created by plastic waste.

Reduce—Immediate Solutions

In 2017, Meituan, the PRC’s leading food delivery giant with 628 million active users and 7.7 million merchants, became the first company to launch the “opt-out for disposable cutlery” feature on its app. Users who choose this option are given points that can be donated to a green initiative fund.

Other food delivery platforms have since followed suit. And the feature has received widespread acceptance. For example, more than 70% of the average 1.2 million daily orders received by Meituan in Shanghai use this feature.

Ele.me, another food delivery platform, has experimented with edible cutlery (Figure 2). The chopsticks are made of flour, sugar, milk, and butter, which customers can eat as desserts. And they come in three tasty flavors: matcha, wheat, and taro. Each pair is covered by recycled paper.

Within the first six months of its launch, Ele.me had attracted more than 100 participating restaurants and distributed 10 million pairs of chopsticks.

Figure 2. Ele.me’s Edible Chopsticks.

Reuse—Midterm Solutions

In addition to the reduction efforts, businesses have experimented with reusable containers. ShuangTi, a startup based in Shenzhen, created an intelligent “shared lunchbox” business model. It employs reusable containers made of highly durable polypropylene with a microchip inserted to track location and usage time.

After an order is placed on the app, the food is delivered to a heat-insulated smart locker (Figure 3) for collection. When it is finished, customers return the containers to the locker. The containers are then gathered, sanitized, and reused for another delivery.

Figure 3. ShuangTi’s Heat-Insulated Lockers.

Since 2017, ShuangTi has delivered over 30 million orders mostly to university students. They estimate that if the project is introduced to 500 campuses, around 5,000 ton of plastic waste could be eliminated each year.

YIKO Eats, a community kitchen startup in Beijing, takes a similar approach by reusing ceramic containers (Figure 4). Customers select a timeslot to return the containers when they place an order. YIKO Eats’ popularity has grown among busy young professionals, who enjoy the coziness of dining in fine china, but dislike the hassle of cooking and cleaning up.

Figure 4. YIKO Eats’ Meals in Reusable Containers.

Recycle and Beyond—Long-Term Solutions

Worldwide, only 1% of polypropylene (the plastic mainly used in delivery containers) is recycled. Oily stains and food residue make the process difficult and costly as the material must be separated and cleaned. As such, containers placed in the recycling bin often end up in landfills or incinerators, representing a major source of pollution.

To address this, Meituan and top chain restaurants have established 350 recycling sites close to customers, typically near office buildings, communities, and campuses, where most orders are placed. The most successful site has a 74% recycling rate.

To turn the waste collected into other useful products, Meituan works with factories to make bicycle baffles (Figure 5), handbags (Figure 6), and cups.

Figure 5. Bicycle Raffles Made from Recycled Containers.

Figure 6. Handbags Made from Recycled Plastic Cups.

Companies have also raced to find a substitute for plastic. Much of this has followed after the government announced to ban the use of disposable plastic in e-commerce, express delivery, and takeaway food by end 2022.

Figure 7. Packaging Film for Cornstarch Containers.

Cornstarch container is biodegradable and a popular substitute, but it is not leak and less oil resistant—less suitable for Chinese food. A smart solution offered by Hualong Packing Materials Co. is to insert a film, made of polyethylene and done by a machine, onto the containers (Figure 7). After a meal is finished, customers can easily remove the film and clean it. Both the film and container can be recycled.

Meanwhile, other companies have also innovated using paper-based materials. Zhongshan Dongyu New Materials Co. has worked with BASF to launch specially designed paper containers (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Zhongshan Dongyu-BASF’s Paper Food Containers.

Stora Enso, a global paper manufacturer, has made containers that are heat and oil resistant (Figure 9). Its products won top honors in Meituan’s Food Delivery Packaging and Incubation Competition in 2021.

Figure 9. Stora Enso’s Paper Containers.

Moving forward, the end of takeaway plastic containers in the PRC is near even amid rising demand for food delivery. More new ideas and products will surely surface as the country strives toward achieving the goal of greener and higher quality development. As in other areas of e-commerce, the PRC’s rich experience provides useful lessons for other developing countries facing similar challenges.

Authors

Hsiao Chink Tang

Senior Economist, ADB

Xiaowei Zhuang

Knowledge Analyst, RKSI, ADB