East Asia Blog Series

Subsidizing Ecofriendly Practices in E-Waste Recycling in the PRC

Jintao Xu and Isao Endo 28 Sep 2021

Electronics manufacturers are held accountable for the full life cycle of their products but receive incentives for proper disposal.

Overview

Households and workplaces in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) generate a large amount of waste from electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE or e-waste). Valuable resources, such as metals and plastics, can be recycled from this waste. However, e-waste recycling businesses in the PRC were competitive only when operated at harmfully low environmental standards that considerably reduced their production costs. This practice caused soil, air, and water pollution.

The PRC adopted the extended producer responsibility (EPR) scheme, which provides incentives for producers to address the environmental impacts of their products over the full life cycle. Manufacturers of electricals and electronics receive subsidies for collecting and disposing their products themselves or outsourcing the work to others. Disposal procedures must meet high environmental standards. Or they can contribute to a national fund that subsidizes environmentally friendly recyclers.

The EPR scheme has promoted the proliferation of standardized disposal and recycling procedures that mitigate environmental impacts and urged manufacturers to adopt environmentally friendly design features that help reduce disposal costs.

Context

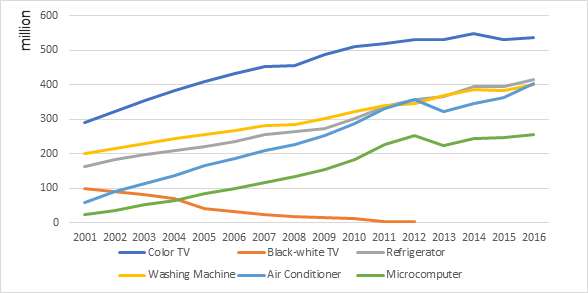

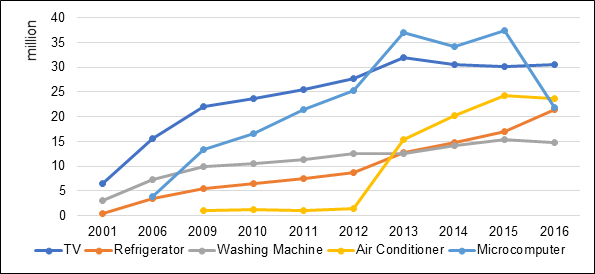

The PRC produces and uses electronics on the largest scale in the world, and it is the biggest market for refurbished and recycled electronics. As shown in Figure 1, the quantity of electrical and electronic products owned by households alone has remained high. Figure 2 shows the number of scrapped electronics estimated from their stocks, assuming a fixed scrapping rate for each year of their lifespan, which is referred to as the “theoretical scrap rate.”

Figure 1: Number of Electrical and Electronic Items Owned by Households

Source: People’s Republic of China (PRC) Household Electronics Appliance Research Institute. 2016. White Paper on the Development of WEEE Recycling Industry 2016 [in Chinese]. Beijing.

Figure 2: Number of Theoretically Scrapped Electrical and Electronic Items

Source: PRC Household Electronics Appliance Research Institute. 2016. White Paper on the Development of WEEE Recycling Industry 2016 [in Chinese]. Beijing.

E-waste has been frequently referred to as “urban minerals,” which reflects its significant value as a resource. However, its recycling and dismantling, if unregulated, could cause considerable damage to human health and the environment. For example, in Guiyu Town, Guangdong province, the dismantling of waste electrical appliances began to flourish as a highly profitable business in the 1990s. Small workshop-type businesses tended to discharge wastewater, waste gas, and solid waste without restriction. This caused soil, air, and water pollution that threatened the health of humans, animals, and plants (NetEase 2009).

Solutions

The PRC addressed the externalities of the profit-seeking dismantling industry by regulating the WEEE recycling industry and promoting environmentally friendly practices creating incentives.

Legislations on recycling

Three laws provide the legal basis and financial incentives for developing a resource- and environment-friendly e-waste recycling industry in the PRC. These are the Circular Economy Promotion Law, Regulations on the Administration of the Recycling of Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment, and Administrative Measures on the Collection and Usage of the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Processing Funds.

The development of the WEEE recycling industry in the PRC has gone through three stages. In the first stage, which lasted until 2009 when the Circular Economy Promotion Law was implemented, collection, dismantling, and disposal of e-waste were largely undertaken by voluntary, yet unregulated, actors despite the existence of a small number of state-financed recycling plants that were intended to demonstrate standardized procedures and techniques. In the second stage (2009 to 2011), the waste was mostly collected by retailers and manufacturers who were backed by state subsidies under the home appliance trade-in policy. This policy also gave rise to more than 100 officially sanctioned and recognized recycling plants that adopted standardized techniques. In the third stage (from 2012 onward), the regulations and the WEEE processing funds, which were implemented in 2012, replaced the trade-in policy as the main legal framework and incentive mechanism for recycling. By the end of 2016, 109 plants received the WEEE processing funds (PRC Household Electronics Appliance Research Institute 2016).

Extended producer responsibility (EPR)

The EPR scheme encourages producers to enhance the environmental performance of their products from design to transportation, consumption, recycling, and disposal.

The WEEE processing funds subsidize the recycling of this type of waste. Producers and importers of electrical and electronic equipment are obliged to pay for disposal costs. In 2015, four government ministries, including the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, issued a notice that urged producers to contribute to recycling and called for the launch of an EPR program. In December 2016, the State Council issued an action plan for implementing this scheme.

Under the program, manufacturers have four areas of responsibility: (i) designing environmentally friendly products; (ii) using recycled materials; (iii) standardizing recycling procedures; and (iv) promoting information disclosure. They can do the recycling and disposal themselves, engage the services of recyclers, or contribute to the WEEE processing funds.

Results

Updated subsidies

From 1 January 2016, subsidy rates of the WEEE processing funds were updated. The rates for television sets and microcomputers were reduced from CNY851 These include newly added renewables to support the phasing out of coal-fired power plants by 2030, industry energy efficiency improvement technologies, and electric vehicles. to CNY60–CNY70 and the rate for air conditioners was raised from CNY35 to CNY130, whereas rates for refrigerators and washing machines remained unchanged at CNY80 and CNY35 (single tub unit) and CNY45 (double tub unit), respectively.

Total subsidies jumped by 4.5 times from CNY750 million in 2013 to CNY3.39 billion in 2014 and increased to CNY5.4 billion (about $833.3 million) in 2015. The number of subsidized firms reached 109 within 3 years. As firms that meet higher environmental standard incur substantially higher recycling costs, they rely on the WEEE funds for profitability and competitiveness. However, the funds have been largely financed by governmental subsidies rather than manufacturers’ contributions. In 2014, the fund’s deficit amounted to CNY2.5 billion ($385.8 million) and was predicted to continue to soar in light of the continuing growth of e-waste (Gu et al 2017). As such, manufacturers were presumed to be inclined to contribute to the fund or turn to less costly recyclers or recycling procedures that have adverse environmental impacts, rather than pay environmentally friendly recyclers the full cost.

Static efficiency

The home appliance trade-in policy was terminated by the end of 2011, but the enhanced producer responsibility system, which was launched in early 2011, did not specify the subsidies until mid-2012. During the gap between the two policies, there was an immediate drop in the volume of WEEE at disposal plants that adopted standardized, yet costly, procedures. However, after the subsidies for producers kicked in, these disposal plants gradually reclaimed and expanded their share of the recycling market.

Efficacy in reaching environmental target

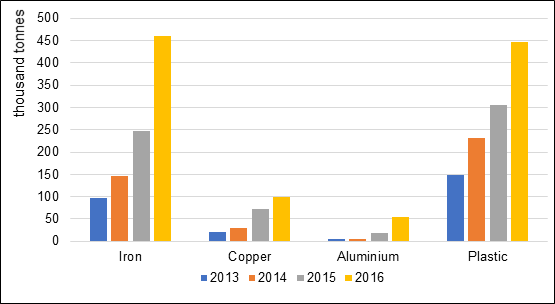

From the outset of EPR implementation in 2012, the value of e-waste as a resource began to materialize. Figure 3 shows that quantities of iron, copper, aluminum, and plastic recycled from waste climbed rapidly from 2013 to 2016.

Figure 3: Resources Recycled by Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Processing Plants

Source: [People’s Republic of] China Household Electronics Appliance Research Institute. 2016. White Paper on the Development of WEEE Recycling Industry 2016 [in Chinese]. Beijing: [People’s Republic of] China Household Electronics Appliance Research Institute.

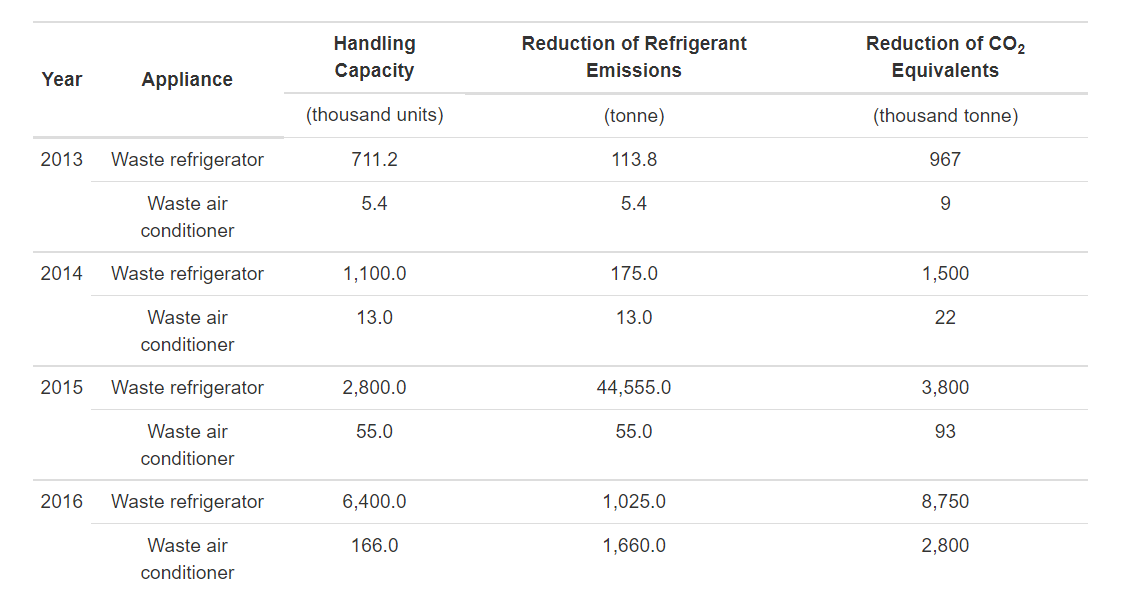

The EPR system has promoted the proliferation of standardized disposal and recycling procedures that mitigate environmental impacts and also urged manufacturers to adopt environmentally friendly design features that help reduce disposal costs. It has delivered a broad range of environmental benefits, such as the reduction of heavy metal emissions and other forms of pollution. Table 1 shows that the discharge of refrigerants from the dismantling of discarded refrigerators and air conditioners has been reduced. Refrigerant emissions are an important source of greenhouse gas (GHG). After the rise in the subsidy rate in 2016, carbon dioxide-equivalent emissions from the dismantling of discarded air conditioners were reduced by almost 30 times compared with 2014.

Table 1: Reductions of Refrigerant Emissions 2013–2016

Source: [People’s Republic of] China Household Electronics Appliance Research Institute. 2016. White Paper on the Development of WEEE Recycling Industry 2016 [in Chinese]. Beijing: [People’s Republic of] China Household Electronics Appliance Research Institute.

1 These include newly added renewables to support the phasing out of coal-fired power plants by 2030, industry energy efficiency improvement technologies, and electric vehicles.

Lessons

Zou et al. (2009) argued for the need to subsidize private recycling businesses to mitigate their environmental impacts by adopting standardized techniques. In the PRC, e-waste recycling is profitable because of loosely enforced environmental regulations, cheap labor, and other contextual factors. Recyclers were reluctant to adopt environmentally friendly yet costly practices. When households sell e-waste to recyclers, these recyclers were bound to pursue maximum profits at the cost of the environment. Subsidies provided the incentive to recyclers to curb environmental damage.

Some argue that EPR may add to the burden of manufacturers. However, Zhou’s (2014) study accentuated the benefits of this system to manufacturers by reducing production costs with the use of recycled materials.

Zhao et al. (2008) believed that many adverse environmental impacts of e-waste disposal are rooted in product design. It is necessary not only to adopt advanced disposal methods but also to design environmentally friendly product features. Before the launch of the EPR scheme, manufacturers were likely to choose a design that reduces production costs or boosts sales but may increase consumer costs at the disposal stage. A subtle merit of the EPR system is that holding manufacturers responsible for the disposal process will make them adopt optimal design features that account for disposal costs, such as designs that may increase production costs but save more in the disposal stage. Manufacturers play a decisive role and are better positioned than any other actor to explore and develop optimal designs.

In addition, complementary policies and regulations can help uphold environmental quality standards and encourage further investments in waste management and recycling infrastructure to effectively implement the EPR system. The PRC’s Catalogue of Solid Wastes Prohibited from Importation includes e-waste in its list of prohibited waste categories, which is complemented by the Prohibition of Foreign Garbage Imports: The Reform Plan on Solid Waste Import Management that bans 24 categories of waste. With restrictions on importing e-waste, many small and informal processors and recyclers saw their operations stifled. Instead, preference was given to larger facilities using state-of-the-art processing and recycling technologies, leading to the development of over a hundred firms specializing in e-waste recycling, many of which belong to major electronics groups of companies (Schulz 2020).

References

Government of the People’s Republic of China [PRC], Ministry of Ecology and Environment. 2012. Administrative Measures on the Collection and Usage of the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Processing Funds (in Chinese). Beijing.

Government of the PRC, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Ecology and Environment, National Development and Reform Commission, and Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. 2015. Subsidy Standards for Waste Electrical and Electronic Products Treatment Fund (in Chinese). Announcement No. 91 (2015). Beijing.

NetEase. 2009. Largest Village Buried in E-Waste: Guiyu, Guangdong Province.

S. Zou and L. J. T. Wu. 2009. Research on Reverse Logistics Mode of Private WEEE in City (in Chinese). Technoeconomics & Management Research. 4. pp. 102–105.

Y. Gu et al. 2017. To Realize Better Extended Producer Responsibility: Redesign of WEEE Fund Mode in [the PRC]. Journal of Cleaner Production. 164. pp. 347–356.

Y. Schulz. 2020. Chinese Engagement Abroad in the Scrap Business. China Perspectives. 2020 (4). pp. 49–-57.

Y. Zhao, C. Wu, and Z. Fu. 2008. Review on Research Progress and Implications of Selecting Responsible Main Part for EPR Based on the Circular Economy Development (in Chinese). Science Research Management. 72 (2). pp. 111–118.

Y. Zhou. 2014. Research on Reverse Supply Chain of Waste Electrical and Electronic Products Recycling Based on Incentive Strategies (in Chinese). (Master). Hangzhou: Zhejiang University.

Author

Jintao Xu

Professor of Economics, Peking University

Isao Endo

Environment Specialist, Environment Thematic Group, Sustainable Development and Climate Change Department, ADB

This blog is reproduced from Development Asia.