East Asia Blog Series

What Can ASEAN Learn from the People’s Republic of China’s Poverty Reduction Strategy?

Xiaoyun Li, Hsiao Chink Tang, and Jin Xu 23 Jul 2019

The experience of the People’s Republic of China shows that beyond economic growth, an adaptive and cooperative approach can help reduce poverty even at hard to reach places.

Analysis

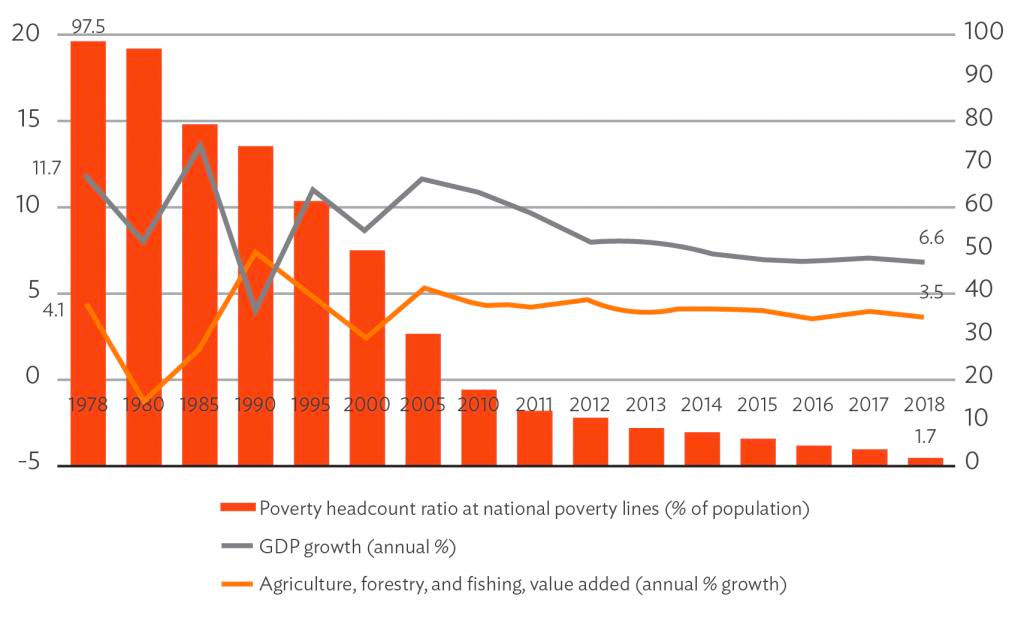

The PRC and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states differ in many respects, but also share similar experiences. Rapid economic growth, as well as social and economic transformations, have helped many to reduce poverty, but they also face similar challenges in rising inequality and lack of growth in the agricultural sector. Lessons from the PRC can guide the design and implementation of poverty reduction strategies in ASEAN countries.

Political and social stability, as well as a consistent development strategy, are important conditions for poverty reduction. Experiences from Cambodia, PRC, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Viet Nam suggest that poverty reduction benefits from long-term systematic government interventions. Improved poverty reduction performance boosts ruling parties’ legitimacy which in turn contributes to a stable political system necessary for implementing long-term development initiatives.

Economic growth is fundamental to poverty reduction. There are two main approaches to poverty reduction: investments in businesses that “trickle-down” to benefit all levels of society, or income redistribution schemes through government interventions. Experiences in the PRC suggest that economic growth can “trickle-down” and reduce poverty if growth occurs in sectors that benefit the poor. In addition, economic growth as a poverty reduction tool is most effective in countries that have relatively equal economic and social situations. As inequality increases, government interventions are needed to ensure the poor benefit from economic growth and to protect those left behind.

Agriculture is indispensable for achieving sustained rural poverty reduction. Agriculture is a primary driver for reducing rural poverty, particularly in countries where most of the population live in rural areas and engage in agriculture-based activities. Improving productivity in the agricultural sector through improved infrastructure, better access to markets, and availability of improved seed varieties and cultivation technologies directly reduce poverty in rural areas. In countries with limited land resources, raising productivity of existing fields is a key method for promoting growth in the sector.

Figure 1: Annual GDP Growth Rate, Annual Agricultural Growth Rate, and Poverty Incidence at National Absolute Poverty Line in the People’s Republic of China

Industrialization can be an effective pathway out of rural poverty. Non-agricultural employment can reduce poverty in rural areas by offering workers another source of income especially during periods of low employment in the cultivation cycle. Rural industrialization becomes increasingly important as agricultural activities decline in relative importance in the wider economy while also increasing rural laborers’ resilience to shocks by diversifying incomes. By offering employment opportunities in small and medium cities, non-agricultural rural enterprises can help slow the expansion of large cities that may not be able to accommodate large influxes of migrant workers.

Targeted governmental interventions can reduce poverty in places where economic growth cannot reach. PRC’s experience suggests that pro-poor interventions can be successful when the trickle-down effects of economic growth weaken and poverty rate is relatively low. The PRC government has channeled diverse resources to support targeted interventions that aim to address the country’s multi-dimensional extreme poverty. Targeted interventions can be industry-based, educational, and cash-transfer social protection approaches. Their selection will depend critically on the accurate identification of the poor, and diagnosis of poverty root causes.

Social protection programs for poverty reduction are more efficient when multi-dimensional poverty increases. In initial stages of economic growth, financial and organizational resources are often limited, thus, social protection programs can hardly be implemented. As growth continues, redistributing income becomes more feasible. And as poverty becomes multi-dimensional, it is increasingly difficult to overcome it merely through economic growth. While many rural families are not poor by the measure of income, they may still lack adequate education or health care that could help sever the inter-generational transmission of poverty. The PRC’s anti-poverty policy that shifts from a developmental approach to an approach combining development and social protection can thus shed some light on when to introduce and how to design pro-poor social protection programs.

Implications

Three approaches to reducing poverty are suggested, namely,

- Identify a strategy to eliminate rural absolute poor through a rapid economic transformation;

- Develop rural areas; and

- Adopt a cooperative approach to understand and address multi-dimensional poverty.

ASEAN countries’ high economic growth rates have been underpinned by robust foreign investments leading to strong employment gains in the manufacturing sector that help countries to reduce poverty. As many ASEAN countries continue to depend on agriculture, there is scope for improvements that will positively affect the rural poor. (World Development Indicators show 7 out of 10 ASEAN member countries have an agriculture sector that accounts for more than 20% of its total employment, and 5 countries have an over 10% agricultural GDP share in 2017). PRC’s experience shows boosting productivity, promoting the rural industry, and developing small cities are key poverty reduction initiatives.

On the other hand, ASEAN can also share useful lessons with the PRC. In particular, Malaysia’s, Singapore’s, and Thailand’s experiences in urban poverty reduction, social protection programs, and rural tourism can help the PRC design and implement better poverty reduction and rural transformation initiatives.

1 M. Ravallion, and S, Chen. 2007. China’s (uneven) Progress Against Poverty. Journal of Development Economics. 82(1). 1– 42.

References

X. Li. 2018. Growth Transformation and Poverty in the PRC and ASEAN. Presentation at 12th ASEAN-China Forum on Social Development and Poverty Reduction. Manila. 27-29 June.

National Anti-Poverty Commission, the Philippines. 2018. Philippine Experience on Poverty Reduction. Presentation at the 12th ASEAN-China Forum on Social Development and Poverty Reduction. Manila. 27-29 June.

M. Ravallion, and S. Chen. 2007. China’s (uneven) Progress Against Poverty. Journal of Development Economics. 82(1). 1– 42.

Authors

Xiaoyun Li

Distinguished Professor at College of Humanities and Development Studies of China Agricultural University

Hsiao Chink Tang

Senior Economist, East Asia Department, Asian Development Bank

Jin Xu

Associate Professor and Assistant Dean, China Institute for South–South Cooperation in Agriculture