East Asia Blog Series

What the People’s Republic of China Can Learn from Japan on Population Aging

Donghyun Park, Cynthia Castillejos Petalcorin, and Shu Tian 4 Apr 2019

An aging population can have a dramatic impact on a country’s economy but Japan has shown that innovative approaches and policies can help mitigate the effects.

The population of the People’s Republic of China is aging rapidly, sparking concerns that the country may grow old before it becomes rich.

The common dictum that “demographics is destiny” captures the notion that an aging population necessarily inflicts a lot of damage on the economy. Japan is often cited as an example by those who subscribe to this view.

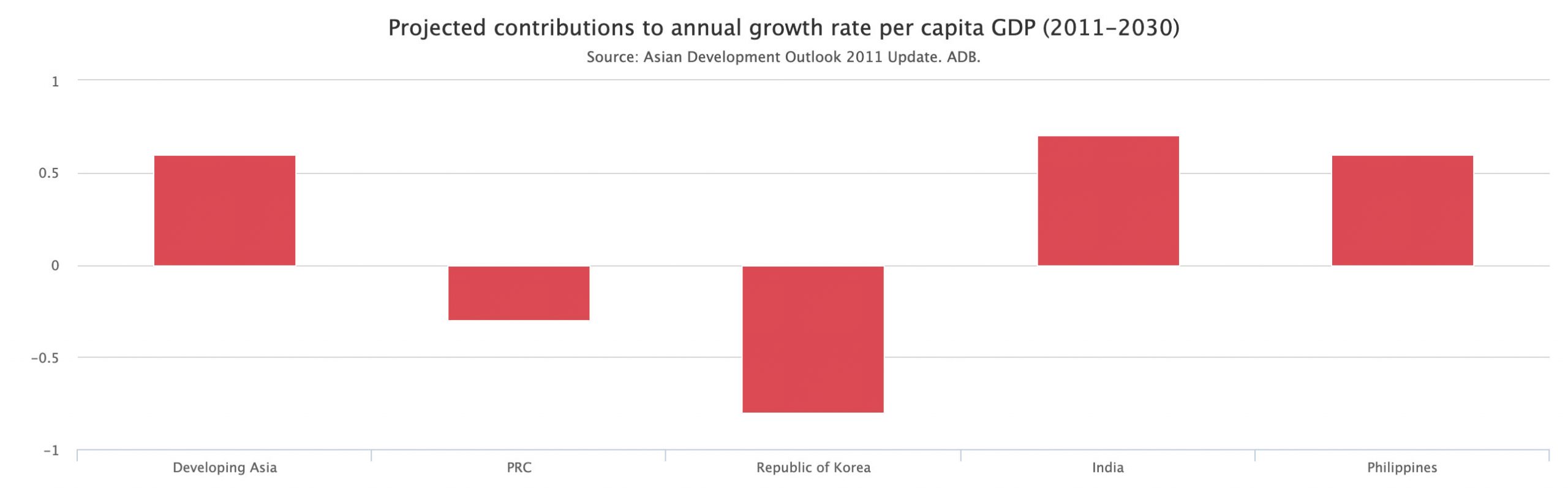

However, as the Japanese experience suggests, there is plenty of scope for the People’s Republic of China to change its demographic fate for the better. (See chart)

One common denominator in the demographic trajectory of the two Asian giants is the sheer speed of population aging.

It took France 114 years and the United States 65 years for the population share aged 65 and older to rise from 7% to 14%. The projected corresponding figure for the People’s Republic of China is 25 years, a similar trajectory to Japan, whose elderly population share shot up from 7% to 14% between 1990 and 2015.

In the past, a relatively young population was a big boon to the People’s Republic of China’s remarkable sustained rapid growth. More specifically, the country’s large and growing labor force delivered an ample supply of workers to the factories that transformed the it into the “Workshop of the World.”

Going forward, however, the demographic dividend that contributed to economic growth over the past 40 years is turning into a demographic tax that is hampering growth.

Simply put, the share of workers in the population is falling while the share of economically inactive individuals is rising. According to ADB research, favorable demographics added 1.2 percentage points to the People’s Republic of China’s average annual GDP growth in 1981-2010 but are projected to subtract 0.3 percentage points in 2011-2030.

Lessons for how a country can adapt to aging population

Economists who worry about the economic impact of the People’s Republic of China’s demographic transition look for cues from Japan’s experience.

In the immediate postwar period, Japan grew rapidly on a sustained basis, much as the People’s Republic of China did later following the market reforms of 1978.

However, since an asset price bubble burst in late 1991 the Japanese economy has been in a prolonged slowdown while its population has aged rapidly.

Not surprisingly, aging is often identified as a contributing factor to the economy’s problems. Nevertheless, it is more accurate to attribute this to difficulties in sufficiently adapting to aging, rather than to aging per se.

To compensate for the slower expansion or reduction of the workforce, each worker in a rapidly aging society must become more productive. Aging can induce technological change that can boost workers’ productivity. In this context, Japan has long been a global leader in robotic innovation and adoption.

Structural reforms—such as slashing business regulations, liberalizing the labor market and agricultural sector, and cutting corporate taxes—could also give a big boost to productivity.

Another strategy to offset a decline in working-age population is to tap new sources of labor, such as women, older workers, and foreign workers. Japan is working on each of these areas but so far without significant progress.

Singapore offers a potential model on immigration. Though like Japan it has seen a sharp decline in fertility, the city-state continues to enjoy solid population growth due to more liberal immigration policies.

The key takeaway is that structural reform is indispensable to avoid a demographic tax from population aging. In the People’s Republic of China, these structural reforms should include the financial sector, mainly improving the efficiency of resource allocation and state-owned enterprises.

Encouraging investment in robotics and other technologies that boost productivity can also mitigate the economic effects of population aging.

Demographics are a powerful headwind, but policy makers in the People’s Republic of China have the tools at their disposal to turn this challenge into an opportunity. Above all, the country must be bold enough to undertake painful but necessary productivity-enhancing structural reforms as well as fully embrace new productivity-enhancing technologies.

Authors

Donghyun Park

Principal Economist, Economic Research and Regional Cooperation Department, ADB

Cynthia Castillejos Petalcorin

Senior Economics Officer, Economic Research and Regional Cooperation Department, ADB

Shu Tian

Economist, Economic Research and Regional Cooperation Department, ADB

This blog is reproduced from Asian Development Blog.