A two-stage holistic and evidence-based framework provides urban planners a structured and practical guide for making cities healthy and age-inclusive.

Introduction

In the future, most people will live in cities and many of them will be older than 60 years old, and as many of these will grow to high ages, a four-generation urban society is emerging. This is a profound transformation and policy and decision-makers must consider and integrate in urban planning and management the health and social needs of densely populated and aging cities, along with other concerns like climate change and environment. Ensuring the well-being and health of people and communities is also a key factor in building a city’s competitiveness, especially considering the increasing potential pandemic threats that we face. The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has shown that determinants of health, like how people live, work, and travel influence populations’ risks to become sick and the ability to recover economically.

A healthy city promotes equality, good governance, well-being, innovations, and knowledge sharing. It involves active mobility, food production, gardening, availability of sports arenas, and ways of social exchange. An age-friendly city enhances the quality of life by anticipating and responding flexibly to the needs and preferences of older persons, and also that of children and other vulnerable groups like the physically impaired. This includes structural aspects like safe and accessible public spaces, sidewalks parks, transport and public buildings, as well as non-structural dimensions like community.

The Authors developed a framework that integrates sustainable urban planning and management with health and age-friendly outcomes and care systems to guide urban planners. The two-stage holistic and evidence-based framework uses two tools: the Health Impact Assessment and Healthy and Age-Friendly City Action and Management Planning. The framework incorporates lessons and best practices from the Asian Development Bank’s projects in the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

This article is based on an online seminar organized by ADB.

Health Impact Assessment

A systematic and evidence-based decision and management support tool, the Health Impact Assessment helps determine how an event, policy, or project can influence health and determinants of health outcomes. It focuses on health promotion and protection to achieve maximum benefits for communities.

ADB has developed two resources to help use this tool. The Health Impact Assessment: A Good Practice Sourcebook provides information on environmental safeguards, poverty and social analysis, and compliance procedures. It aims to ensure that health risks and opportunities are considered in project planning, approval, and implementation. A Health Impact Assessment Framework for Special Economic Zones in the Greater Mekong Subregion helps countries identify and manage health risks and opportunities associated with economic growth and development.

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the need to make Health Impact Assessments more holistic, practical, and action-oriented. The crisis is linked to urban health issues, such as bad air quality, lack of decentralized health care, poor transport, and dense urban areas. This raises the need to move from risk mitigation to a more proactive approach to improving the community health and well-being in cities.

Healthy and Age-Friendly City Action and Management Planning

This tool builds on the results of the impact assessment; prioritizes actions and investments; identifies roles and responsibilities, financial and human resource requirements; and sets a management and action plan to maximize positive health opportunities based on data from feasibility studies, scoping activities, baseline information, business cases, and strategic frameworks.

It follows three steps. The first involves ranking risks and evaluating the list of health risk mitigation options in close collaboration and consultation with city leaders, stakeholders, and communities. The projects are prioritized based on technical feasibility, social responsiveness, and financial and economic viability. The second step covers the preparation, financing, and implementation of health management plans, which will be the blueprint for improving the urban environment. The last step involves monitoring and evaluation, which includes regular surveys on health improvements, healthy city profile updates, cost and benefit assessment, and identification of gaps in operation or design.

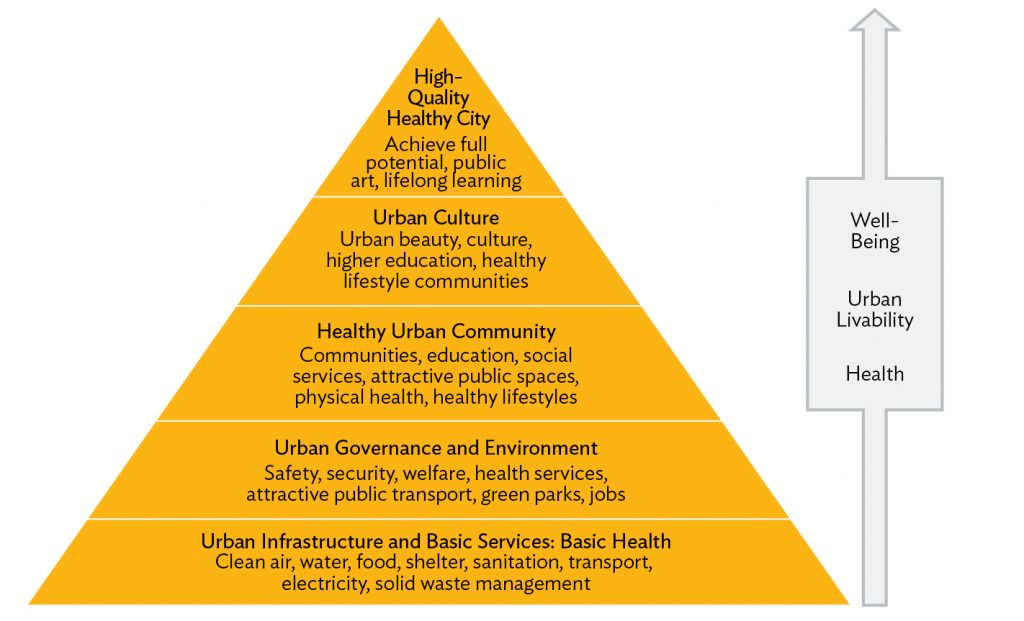

Hierarchy of Needs

The basic concept behind these tools is that public health needs and objectives in cities follow the hierarchy of needs principle:

- Basic needs of residents come first for less developed cities.

- More advanced health needs associated with lifestyle options are prioritized for more developed cities.

- A high level of well-being is achieved for all residents.

Based on a modified version of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs framework, the basic urban structure at the bottom requires clean air, water, and shelter as basic services. At the top is a High-Quality Healthy City that enables residents to achieve their fullest potential through services and facilities that enhance well-being, urban livability, and health. This is achieved through a holistic and integrated approach to urban planning and management and involves the active participation of stakeholders.

Figure 1: A Framework for Attaining a Healthy and Age-Friendly City

Source: Authors. Based on the theory of a hierarchy of needs by A.H Maslow. 1943. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review. 50. pp. 370-96.

Using the hierarchy of needs as a roadmap, the impact assessment addresses the needs and challenges of specific age groups while the planning tool prioritizes projects and investments based on data. Plans for financing, implementation plan, and monitoring are developed in this iterative approach. The two-stage framework primarily aims to provide a structured and practical guide to assess health and aging needs, challenges, impacts, and opportunities of existing urban areas and of new urban developments. This will help make health and age-friendly city planning easier.

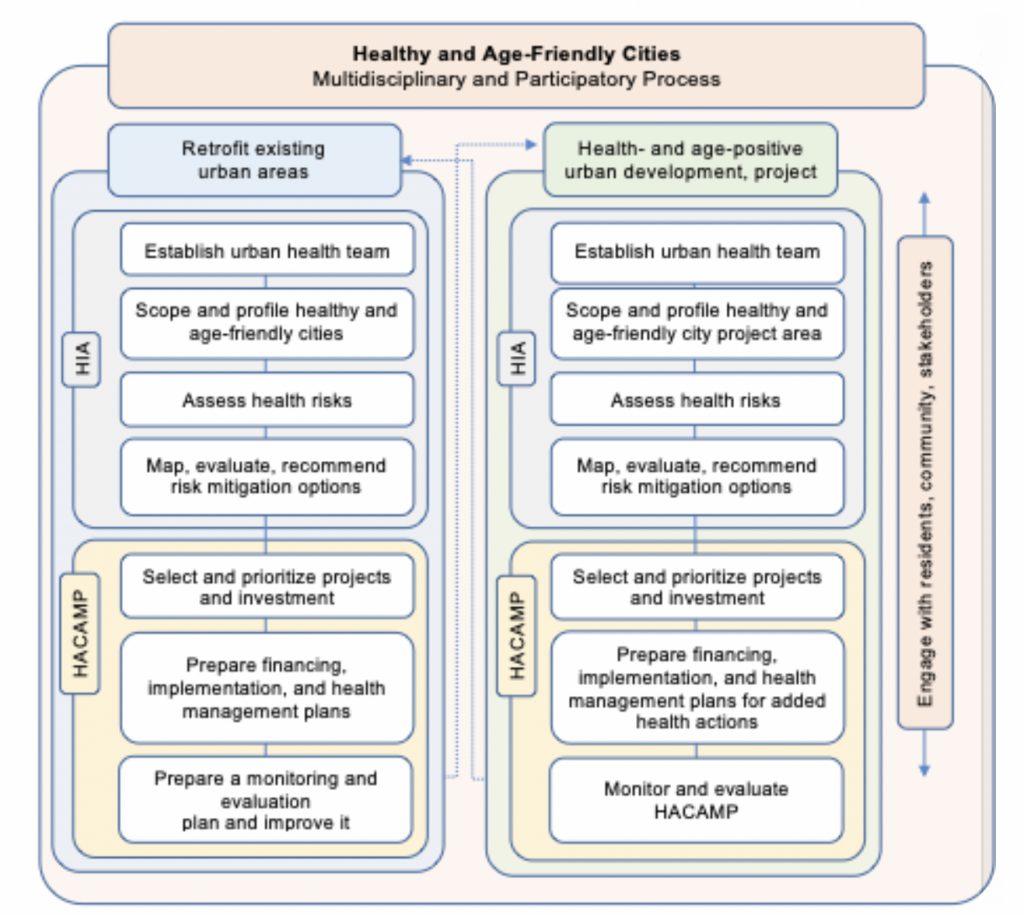

As shown in the process diagram below, the left side is for urban rehabilitation and retrofitting existing cities and urban areas while the right side is for urban master plans and new projects. Residents, communities, and stakeholders are engaged throughout the whole process. By linking the impact assessment with the planning tool, a financing and implementation plan of priority actions based on consultations is produced, and then monitored and evaluated.

Figure 2: Healthy and Age-Friendly Cities Multidisciplinary and Participatory Process

HIA=Health Impact Assessment, HACAMP=Healthy and Aged-Friendly City Action and Management Plans. Source: Authors.

Here is a step-by-step example of how the framework may be used for existing urban areas:

- Establish an inter-disciplinary cross-sector urban health team. Get the support of champions. Raise awareness among sectors. Create a steering committee, usually led by a city mayor.

- Define geographical scope and urban health issues to investigate. Gather data, assess gaps, develop databases, analyze data, and develop a healthy city profile.

- Compile registry of and prioritize risks, impacts, and opportunities. Formulate options for aspirational goals against each risk, impact, and opportunity.

- Map all structural and nonstructural options to mitigate risks and leverage health benefits. Evaluate (including a cost-benefit analysis) and recommend risk mitigation options to the steering committee.

- Prioritize structural and nonstructural options to minimize adverse health risks and maximize health benefits in consultation with leaders, stakeholders, and the community.

- Prepare financing and implementation plans, establish priority actions, and finalize plans after public consultations.

- Prepare monitoring and evaluation plans for implementation, continue regular monitoring, and review and improve the Healthy and Age-Friendly City Action and Management Plan.

Implementation in the People’s Republic of China

The PRC launched in October 2016 a program that calls for a “health in all” policies approach to help prevent and treat diseases and promote healthy lifestyles. A practical and flexible framework can help implement the health-focused program in cities and prioritize the health and aging experiences and outcomes of urban residents.

ADB has applied the framework to two projects in the PRC. The first one was for the Yunnan Lincang Border Economic Cooperation Zone Development Project. Based on the results of the rapid Health Impact Assessment, recommendations were made to address several health issues that included the risk of communicable disease transmission, demand for local health services, and road safety. Next, a public health management plan was initiated under this project not only to mitigate the infectious disease risk but also improve to the overall health and well-being of the people.

The second project is the Jilin Yanji Low-Carbon Climate-Resilient Healthy City Project. Located in Yanji city, the project focused on improving urban livability of the medium-sized city through the integration of public transport, non-motorized transport, and green spaces, and improvement of the water supply and wastewater management systems. A baseline assessment of health determinants and risks and adverse impacts of the project was conducted, and it identified challenges and opportunities for improved health outcomes. Meanwhile, the project will implement a Healthy and Age-Friendly City Action and Management Plan that will focus on controlling communicable diseases, significantly reducing non-communicable diseases, promoting healthy lifestyles through health care services, and establishing urban and building design features that provide access to people of all ages.

The initial target of the framework was the PRC, but it can also provide guidance to other countries. It is relevant for cities at all development stages, especially in view of the COVID-19 pandemic and demographic trends.

References

ADB. 2018. ADB Loan Supports Cross-Border Trade, Urban Services in Yunnan, PRC.

ADB. 2018. A Health Impact Assessment Framework for Special Economic Zones in the Greater Mekong Subregion. Manila.

ADB. 2018. Health Impact Assessment: A Good Practice Sourcebook. Manila.

ADB. Jilin Yanji Low-Carbon Climate-Resilient Healthy City Project.

ADB. Yunnan Lincang Border Economic Cooperation Zone Development Project.

N. Habib, S. Rau and S. Roth. 2020. Healthy and Age-Friendly Cities in the People’s Republic of China. Webinar. 14 May.

N. Habib, S. Rau, S. Roth, F. Silva, and J. Shandro. 2020. Healthy and Age-Friendly Cities in the People’s Republic of China: Proposal for Health Impact Assessment and Healthy and Age-Friendly City Action and Management Planning. ADB East Asia Working Paper Series. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

World Health Organization. 1985. Promoting Health in the Urban Context. WHO Healthy Cities Project.

WHO. 2007. Global Age-friendly Cities: A Guide. France.

Authors

Najibullah Habib

Health Specialist, East Asia Department, ADB

Stefan Rau

Senior Urban Development Specialist, East Asia Regional Department, ADB

Susann Roth

Principal Knowledge Sharing and Services Specialist, Sustainable Development & Climate Change Department, ADB

This blog is reproduced from Development Asia.