Creating a Successful New City Development Within a City Cluster: Global Knowledge and Insights for Xiong’an in the PRC

An integrated, green, and people-centric urban development strategy can help make cities inclusive and sustainable.

Overview

Like other provinces in the PRC coping with rapid urbanization, Liaoning is facing the challenges stemming from rural–urban migration, such as poor infrastructure, pollution, unemployment, inadequate public services, and poverty.

Recognizing that current urbanization trends will place excessive pressure on the provincial capital of Shenyang, the Liaoning provincial government saw the need to enhance infrastructure and services in key townships and cities.

A project funded by the ADB supported the province by implementing a sustainable solution to address these challenges through targeted infrastructure improvements in wastewater management, sanitation, heating, and transport services.

Project snapshot

Context

Liaoning province is in the northeastern region of the PRC. Its geographical center includes a cluster of cities and historical industrial bases. The urban population is expected to reach 85% of the total provincial population by 2050 from 65% before 2012, largely because of migration from rural areas.

The province has been lagging in economic growth because of the depletion of natural resources, the decline of heavy industries, and the pressures of rapid urbanization. Meeting the increasing demands on urban infrastructure, municipal services, and employment is a critical issue that needs a holistic solution.

Challenges

Among the challenges faced by many of Liaoning’s cities and towns are poor infrastructure, pollution, the degraded water quality in the Liao River, and a large population of rural migrants and laid-off workers with obsolete skills.

The service breakdowns of old district heating facilities made the lack of heating a grave concern in winter, affecting women who are primarily responsible for housekeeping and caring for the sick and the elderly. Poor road conditions and lack of public transport services restricted people’s mobility for economic opportunities.

In addition to gaps in existing infrastructure, municipal services were often of poor quality or limited—directly affecting the living conditions of residents, particularly those in towns or small cities. This requires substantial effort to enhance the institutional capacities of local governments and municipal service providers if towns are to reach their full development potential.

Solutions

An ADB-financed project implemented an integrated, green, and people-centric urban development strategy through targeted wastewater management, district heating, and urban transport development in key townships in central Liaoning province.

Promote people-centric infrastructure services and facilities

The project selected key townships and cities around the provincial capital, Shenyang, which has a population of 7.4 million to promote concentrated urbanization through towns and urban clusters development. Shenbei and Benxi are in the core Shenyang metropolitan area; Fuxin, Gaizhou, and Xinmin are along intercity connection belts outside the Shenyang metropolitan area; while Heishan and Huanren are included to strengthen rural links with urban areas.

The project constructed wastewater management systems to address the deterioration of the water quality of the Liao River, one of the seven river basins of the PRC. A wastewater treatment plant was also constructed in Shenbei new district (Xinchengzi Town) with a capacity of 25,000 cubic meters per day, 4.59 kilometers (km) of sewer pipes, and 7.89 km of stormwater pipelines. The treatment plant became operational in June 2019 and is fully utilized by 2021.

The project improved the district heating services of the Fuxin urban area by replacing small boilers and heating stoves in individual households. New primary and secondary heating pipelines totaling 20.76 km were constructed. The 20.9 km secondary heating network and 74.3 km tertiary heating pipes were upgraded. Fifty thermal stations were installed, and one heat exchange station was constructed. The project expanded district heating area by 3.1 million square meters in Fuxin.

The project promoted the development of environmentally sustainable urban infrastructure, which included upgrading and constructing roads, alley, and bridges; improving stormwater pipelines and sewer coverage; installing energy-saving lighting; and expanding public green areas.

Along with the road construction, the project laid out of 105 km of stormwater pipes, 25 km of sewers, and 25 km of water supply pipelines. The integrated approach significantly reduced both the construction costs and implementation period.

The project adopted holistic and inclusive road designs, bus priority lanes, and road safety features, such as traffic-calming measures and separate nonmotorized transport lanes. The roads constructed under the project included not only trunk urban roads and key bridges but also a considerable number of alleys and sidewalks, most of which serve the previously neglected corners in the urban area.

Enhance the capacities of local government officials in urban planning and management

Officials and staff of key government bureaus were trained in various aspects of eco-friendly urban planning, financial management, environmental management, and inclusive urban governance, particularly in the fields of transportation, heating, and sewage treatment.

Locals learned modern technologies to reuse the methane and waste heat from sewage. Intelligent heating control systems were introduced to reduce energy consumption of district central heating facilities.

The project also conducted a training program to promote social inclusion and equitable access to public services and economic opportunities, including jobs, for disadvantaged groups while promoting efficient use of resources and keeping local government finances prudent and sustainable.

Results

Improved urban infrastructure services

The project has contributed to improved sanitation, clean water supply, reliable and clean heating, and enhanced urban road linkages and related facilities in seven key townships and cities in central Liaoning. More than 1.6 million residents, of which 40% were women, benefited from the project. It enhanced the quality of life of the residents and promoted more competitive, green, and inclusive cities.

The improved district heating network have helped dispose individual heating stoves for about 5,079 households or 11,630 people. As a result, women and children have less exposure to pollutants from household heating stoves; fewer domestic chores and less time spent for space heating; and a lower incidence of respiratory diseases related to indoor air pollution.

Improved air and water quality

The operation generated significant environmental benefits in the project areas. The actual days of air quality equal to or above grade II increased to 309 days per year in 2019 from 265 days per year in 2011. The wastewater collection rate increased to 90% from 43% during the same period. The Fuxin district heating component decreased the use of standard coal of 27,771 tons and avoided 69,242 tons of annual carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from 2019.

Through the urban road subprojects, better road condition and shorter travel times reduced fuel consumption, leading to a decrease of more than 56,760 tons of CO2 emissions per year.

The downstream water quality of the Changhe River (a branch of Liao River) and Qixing Wetland were significantly improved because of enhancements in wastewater and solid waste treatment facilities. Pollutants were reduced by more than 1,616 tons of chemical oxygen demand, 645.4 tons of biochemical oxygen demand, 23.5 tons of total phosphorus, 260.0 tons of total nitrogen, and 168.4 tons of ammoniacal nitrogen per year. The Qixing Wetland, the largest wetland park in urban areas in the country, contributes to biodiversity conservation by supporting a diversity of wetland plants, animals, and waterbirds. The wetland has been turned into a public park for residents to enjoy the green and pleasant scenery.

Lessons

Implementing an integrated urban development strategy helps promote the efficient development of livable, inclusive, green, and sustainable cities. People-centric principles in project design promote social inclusion and equitable access to urban services. Holistic road designs, road safety features, and bus priority lanes can help make services more inclusive to vulnerable populations, particularly women and the elderly.

Urban development projects are also particularly effective when accompanied by capacity development programs for key government officials to strengthen urban management and service delivery.

ADB. 2021. Completion Report: Integrated Development of Key Townships in Central Liaoning in the People’s Republic of China. Manila.

ADB. 2018. Completion Report: Liaoning Small Cities and Towns Development Demonstration Sector Project in the People’s Republic of China. Manila.

ADB. 2012. Completion Report: Liaoning Environmental Improvement Project in the People’s Republic of China. Manila.

Senior Project Officer (Financial Management), East Asia Department, ADB

This blog is reproduced from Development Asia.

Nigel Crisp, a crossbench member of the House of Lords, the UK, and former Chief Executive, National Health Service, will share insights on how people of all walks of life can play to build a healthy and health creating society.

The right blend of public and private sector support, along with long-term transport strategies and anchor institutions such as schools and hospitals, are some of the basic ingredients needed for a successful new city.

The United Nations estimates that 60% of the world’s population will live in cities by 2030. People tend to flock to long established cities which causes overpopulation in megacities. Today, one in five people worldwide lives in a city with more than 1 million inhabitants and this is growing. One solution to the overpopulation in megacities is to plan and develop new cities. Since 2000, more than 40 countries have built more than 200 new cities.

Strategically located, purpose-built cities are intended to become tomorrow’s trade, finance, logistics, technology, or commercial centers, focusing on long-term economic growth that could challenge existing global networks. Some examples of new city developments include Xiong’an New Area in the People’s Republic of China, designed to become a hub for research, education, and high technology research and development; Sri Lanka’s Colombo Port City, envisioned as a major financial center in the sub-continent; and Sejong, Republic of Korea, which is being built to relocate the central government functions from Seoul.

How can we gauge if a new city will become successful in achieving its primary development objectives? Looking at several city developments, there are several factors for success:

Presence of anchor institutions and transport infrastructure. Basic facilities such as schools, hospitals, and shopping centers should be developed and supplied in time to attract residents. Irvine in Southern California was planned to include a branch of the University of California which made the city grow. Also, transportation channels such as highways and mass transit systems must be available.

Land development can also be coordinated with rail investments. A housing development in Tama, Japan, was planned and built together with the rail line, and this contributed to its growth.

There should be a balance for both the supply of infrastructure and the demand for it. Developers must be cautious about over-building before there is demand and delayed supply of infrastructure and services that could slow down the growth of new cities. For example, the construction of rail transit in Tsukuba lagged in the early years, resulting in time-consuming traffic and relatively weak connection with Tokyo.

Strong central and local government policies. Governance structure and support plays a role in new city growth. New developments rely on support from higher levels of government, often including compulsory land expropriation, the establishment of a specialized development company, and financial support. Stable government support is essential for the success of the new city.

However, higher level government leadership or central government policy could change over the course of the development, which risks the momentum of growth, as in the case of Sejong in the Republic of Korea. Sejong was planned to become the new capital and promote the regional development of other areas of the country. However, a court ruled that the capital must remain in Seoul in response to a complaint filed by the main opposition.

The sustainability of new city growth is always a challenge.

Since then, Sejong has lost its momentum, and the relocation is only half-done. A new city’s access to central government support is a big plus, but strong local institutions are needed for the area to grow its capacity and adapt to the evolving environment. Tsukuba, the city of science near Tokyo, illustrates the importance of local capacity development for sustained growth. The story of Tsukuba’s development suggests two key factors: strong support from the central government, and local strategies that are responsive to the changing circumstances. The former is key to the success for Tsukuba’s development in the first two decades, and the latter is essential for its sustained growth into today.

Enabling environment that allows business sector to flourish. While government planning and public sector expenditure is essential for new city growth, they alone are far from sufficient to grow a prosperous city. The ability of the private sector to participate and function smoothly is also an important dimension of new city development. In the United States, private developers have led the development of many successful suburban cities.

In the People’s Republic of China, Shenzhen’s success significantly benefited from the presence of an active private sector. The ability of the government to attract the private sector to work together has set the tone for new cities to grow. Kunshan, also in the People’s Republic of China, stands out because of the local government’s continuous willingness to innovate its services for the business sector.

The stories of Shenzhen and Kunshan show how local institutions, enabled by high-level governments or local governments, have laid down the foundation for the private sector to prosper. Some typical policies to attract private sector development include tax reductions and exemption for new businesses or high-tech companies.

Natural endowment is important but not a dominating factor. The natural attributes of an area are often perceived as an attraction for residents to move to a new development. Irvine in California, like other cities in Southern California, has been praised for its natural environment. Lake Kasumigaura, the second largest lake in Japan is located near Tsukuba. The presence of natural land or waterscapes is an advantage however, this is rarely a leading factor for a new city’s success. New cities tend to be planned at sub-prime locations because better locations have been already developed. If the other factors are present, natural endowment is not crucial to develop a new city.

The sustainability of new city growth is always a challenge. The economic environment may change, a rival city may thrive and compete, local residents and businesses may leave, and political support may disappear.

To address this, during the inflow of resources at the start of a new city development, leaders should lay out a clear path for local institutions to develop and take the lead. Local government, therefore, must constantly update its strategies and continually pursue an environment for the private sector to flourish.

The process of city development is complicated and dynamic but key factors can guide developers toward a sustainable and vibrant city.

Senior Transport Sector Officer, East Asia Department, ADB

This blog is reproduced from Asian Development Blog.

Ecosystem-based adaptation solutions can reduce vulnerability and build resilience of urban areas to climate change.

Introduction

Redeveloping urban areas through climate adaptation measures can make cities more resilient to the hazards of extreme weather and better cope with water surplus or shortage, heat stress, and land subsidence. Moreover, implementing such measures can result in co-benefits for public health, biodiversity and social well-being.

Cities are designed according to current or past conditions. Land-use changes because of continuous population growth. Urbanization can lead to reduced infiltration, increased runoff and water demand, and urban heat island effect. This urbanization leads to reduced infiltration, increased runoff and water demand, and urban heat island effect. Climate change can also magnify existing risks and vulnerabilities of urban areas to flooding, drought, and extreme heat.

Soil and vegetation naturally absorb 90% of rainfall through infiltration into the ground and evaporation into the air, while hard city surfaces like asphalt, pavement, and roofs rapidly shed water, creating huge volumes of fast-flowing runoff. Developed areas create over 500% more runoff than natural areas of the same size.

Ecosystem-based (or nature-based) solutions have been developed over the past decades in response to the growing need to improve urban resilience as well as environmental sustainability. Digital tools, such as the Climate Resilient City Tool, are available to help urban planners evaluate climate risks and promote collaboration of stakeholders for ecosystem-based adaptation measures.

What is ecosystem-based adaptation?

Inspired and supported by nature, ecosystem-based adaptation measures are cost-effective solutions that harness ecosystem services to reduce vulnerability and increase the resilience of cities to extreme rainfall, drought and heat–aggravated by climate change. Ecosystem-based adaptation measures follow the basic principles of conservation, sustainable management, and restoration of ecosystems. These include soft and hard engineering measures to develop green or hybrid (green–blue–grey) solutions that integrate plants, water systems, and green infrastructure. They provide environmental, social, and economic co-benefits and help people adapt to the impacts of climate change.

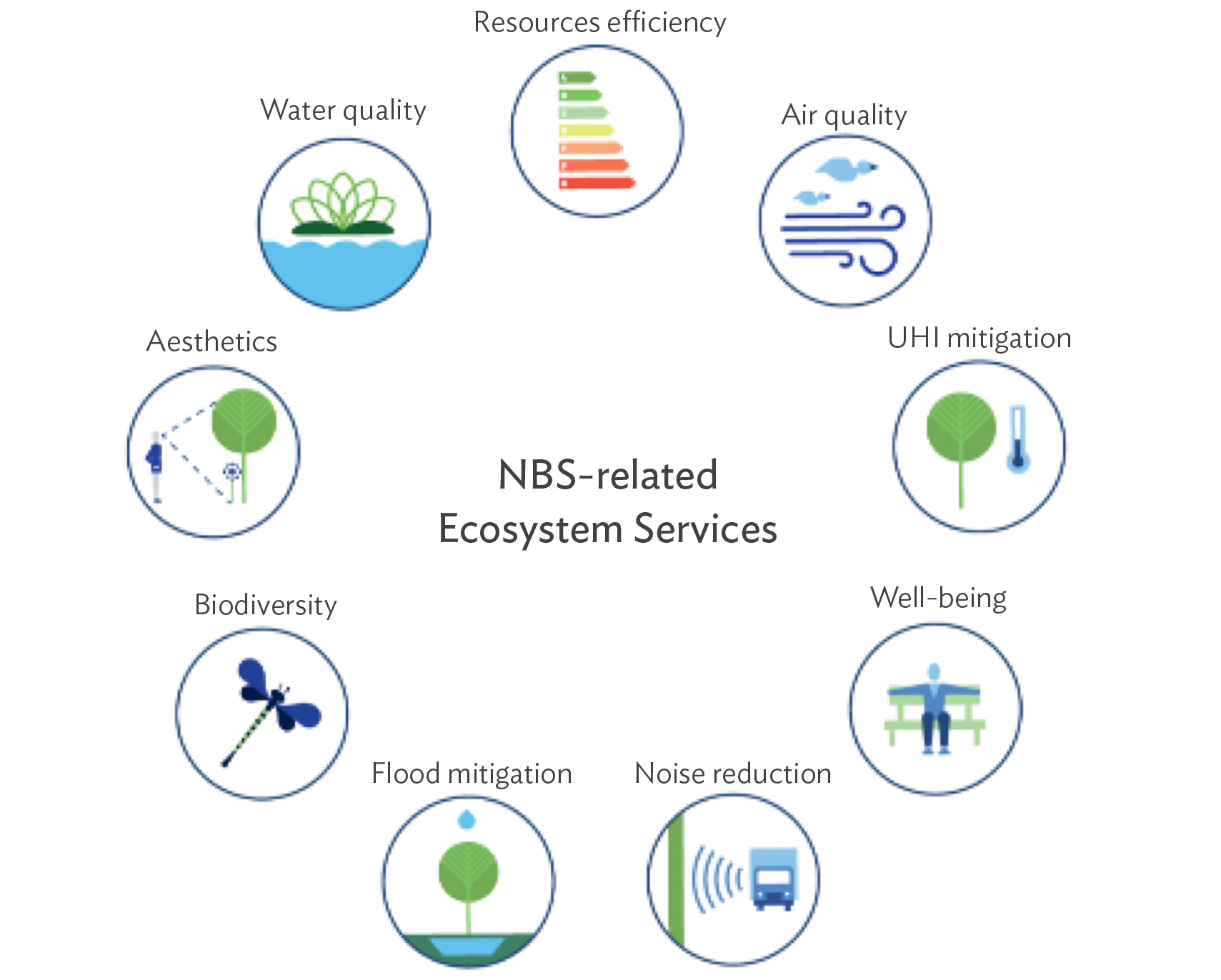

Figure 1: Ecosystem Services of Nature-Based Solutions

Measures that promote ecosystem-based adaptation improve a city’s climate resilience by enhancing infiltration and evapotranspiration,2 and capturing and reusing stormwater. The goal is to restore a city’s capacity to harvest, absorb, infiltrate, purify, store, use, drain, and manage rainwater. They mitigate the water discharge from heavy rainfall, retain and degrade pollutants, reduce the amount of stress on a city’s wastewater treatment facilities, and help maintain the natural water cycle. Examples of these measures include green roofs, porous pavements, raingardens, bioswales, rainwater tanks, smart irrigation, and urban forest. (See the examples of 43 ecosystem-based adaptation measures.)

Environmental, social, and economic co-benefits derived from ecosystem-based adaptation measures include:

Apart from improving the city’s livability and creating a healthier and more attractive city, ecosystem-based adaptation activities can further contribute to the sustainable use of energy and urban resources while enhancing the urban ecosystem and biodiversity. Through urban regeneration, they can help revitalize neglected areas and increase land value and government revenues. Recreational spaces that use ecosystem-based adaptation measures improve people’s well-being and create tourism services, that in turn, can create jobs and stimulate local economies.

What is the Climate Resilient City Tool?

Urban climate resilience planning involves multiple participants. Planning, implementation, and maintenance of ecosystem-based adaptation measures require the cooperation of city bureaus and departments, each with the need to adapt their policies, procedures, regulations, and practices.

In order to support cities in climate resilience planning and design, there are science-based tools available for hazard exposure and vulnerability analysis. Some tools present an overview of potential solutions and/or best practices to mitigate the risks. One of these tools is the Climate Resilient City Tool, an information and technology-based urban resilience and adaptation planning support tool that was developed by Deltares to assess climate risks, identify key flood-prone areas, and support collaborative spatial planning of ecosystem-based adaptation measures. The web-based tool can be accessed using a touchscreen device for collaborative design planning or a single personal computer to individually explore adaptation options.

The Climate Resilient City Tool provides an initial quantitative estimate of the resilience capacity improvement, co-benefits, and associated costs of the proposed adaptation measures. This will allow design participants to collaboratively explore alternative choices and come up with an initial concept. The initial design can then be used as input for a more detailed design of the landscape and drainage plan of the project area.

It facilitates dialogue among stakeholders to identify priority areas for climate resilience improvement. Policymakers, government authorities, planners, designers, and practitioners can work together to determine the requirements of the priority areas and set the adaptation targets. It is a user-friendly way to practice collaborative city development planning that allows representatives from various bureaus and organizations to discuss multi-disciplinary concerns, co-create adaptation scenarios, and co-design a conceptual plan of a resilient and attractive blue-green infrastructure for a community. With detailed information provided for 43 ecosystem-based measures, design participants can select specific interventions that can be implemented at the street or block level.

Ecosystem-based Adaptation Measures in an ADB Project

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) supported the preparation of a localized version of the Climate Resilient City Tool for the city of Xiangtan in Hunan Province, People’s Republic of China. Information on the effectiveness and costs of ecosystem-based adaptation measures have been adjusted for local conditions.

Xiangtan is an old industrial city undergoing rapid urbanization and industrial transformation. Some areas have been experienced flooding because of increased rainfall and drainage capacity has been exceeded. The Climate Resilient City Tool, developed in English and Chinese, was used in the project preparation of the urban climate resilience component of the Xiangtan Low Carbon Transformation Sector Development Program. A flood hazard map was generated for Xiangtan based on an analysis of local conditions.

Climate resilience experts trained local government authorities and other stakeholders on urban hazards and challenges, urban climate resilience, adaptation planning, and nature-based solutions, including ecosystem-based adaptation measures. In the design workshop, participants used the Climate Resilient City Tool to prepare a concept design for two project areas.

A new hospital to be constructed in Xiangtan is located in a critical flood-prone zone and requires more than 5,000 cubic meters of retention, detention, and storage capacity for pluvial flood protection. The concept design considered several ecosystem-based adaptation measures, including rainwater gardens, systems for rainwater harvesting, catch pits, permeable pavement, urban wetlands, and green roofs. These measures aim to create large peak storage volumes for drought resistance and flood protection, as well as improve runoff water quality and enhance green spaces.

Initiatives to be implemented on and along one of the main roads involve converting trees to tree pits, creating rain gardens for treating stormwater from the side pathways, modifying or relocating catch pits to new rain garden areas, creating porous pavement for cycle lanes and pedestrian walkways, and developing subsurface infiltration for water storage under cycle lanes and pedestrian walkways. These will improve infiltration, reduce runoff pollution, decrease drainage and peak volumes of stormwater, and improve the landscape and street aesthetics. These will help strengthen biodiversity and support Xiangtan’s transition into a “sponge city.”3

Conclusion

Ecosystem-based adaptation measures are among the most effective ways of advancing climate resilience by integrating the use of biodiversity and ecosystem services while maximizing co-benefits.

Collaborative city development planning is needed to discuss multi-disciplinary concerns and co-create conceptual plans for a resilient and attractive city.

Applications of the Climate Resilient City Tool in various settings and contexts in several cities have illustrated the added value of the toolbox in bringing policy and practice together with the help of science for a more water-robust and climate-resilient urban environment.

ADB. 2020. $200 Million in ADB Loans to Demonstrate a Low-Carbon and Resilient City Growth Model in Xiangtan, PRC. News Release. 13 October.

ADB. China, People’s Republic of: Xiangtan Low-Carbon Transformation Sector Development Program.

Deltares. Climate Resilient Cities Toolbox.

Deltares. Ecosystem-based Adaptation Measures Available in the Xiangtan Climate Resilient City Toolbox.

Senior Urban Development Specialist, South Asia Department, ADB

Team Leader, Urban Land & Water Management, Deltares

Urban Water Management Specialist, Deltares

This blog is reproduced from Development Asia.

A two-stage holistic and evidence-based framework provides urban planners a structured and practical guide for making cities healthy and age-inclusive.

Introduction

In the future, most people will live in cities and many of them will be older than 60 years old, and as many of these will grow to high ages, a four-generation urban society is emerging. This is a profound transformation and policy and decision-makers must consider and integrate in urban planning and management the health and social needs of densely populated and aging cities, along with other concerns like climate change and environment. Ensuring the well-being and health of people and communities is also a key factor in building a city’s competitiveness, especially considering the increasing potential pandemic threats that we face. The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has shown that determinants of health, like how people live, work, and travel influence populations’ risks to become sick and the ability to recover economically.

A healthy city promotes equality, good governance, well-being, innovations, and knowledge sharing. It involves active mobility, food production, gardening, availability of sports arenas, and ways of social exchange. An age-friendly city enhances the quality of life by anticipating and responding flexibly to the needs and preferences of older persons, and also that of children and other vulnerable groups like the physically impaired. This includes structural aspects like safe and accessible public spaces, sidewalks parks, transport and public buildings, as well as non-structural dimensions like community.

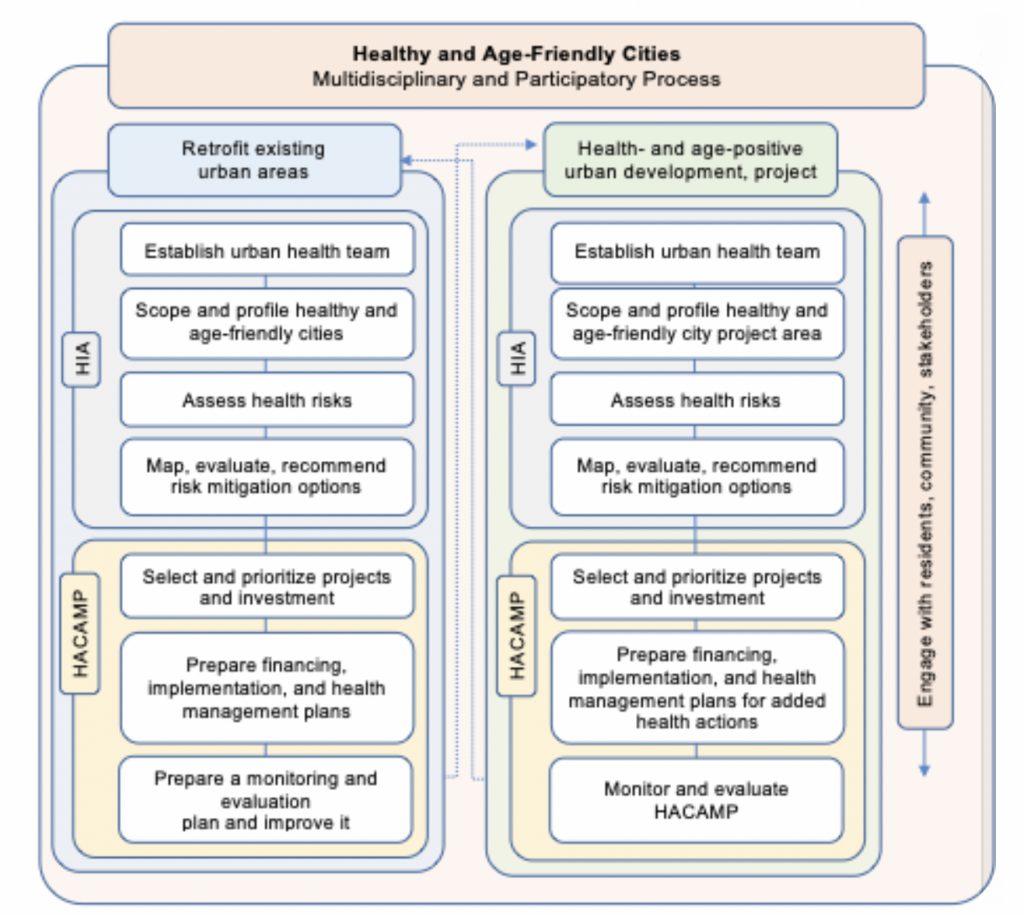

The Authors developed a framework that integrates sustainable urban planning and management with health and age-friendly outcomes and care systems to guide urban planners. The two-stage holistic and evidence-based framework uses two tools: the Health Impact Assessment and Healthy and Age-Friendly City Action and Management Planning. The framework incorporates lessons and best practices from the Asian Development Bank’s projects in the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

This article is based on an online seminar organized by ADB.

Health Impact Assessment

A systematic and evidence-based decision and management support tool, the Health Impact Assessment helps determine how an event, policy, or project can influence health and determinants of health outcomes. It focuses on health promotion and protection to achieve maximum benefits for communities.

ADB has developed two resources to help use this tool. The Health Impact Assessment: A Good Practice Sourcebook provides information on environmental safeguards, poverty and social analysis, and compliance procedures. It aims to ensure that health risks and opportunities are considered in project planning, approval, and implementation. A Health Impact Assessment Framework for Special Economic Zones in the Greater Mekong Subregion helps countries identify and manage health risks and opportunities associated with economic growth and development.

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the need to make Health Impact Assessments more holistic, practical, and action-oriented. The crisis is linked to urban health issues, such as bad air quality, lack of decentralized health care, poor transport, and dense urban areas. This raises the need to move from risk mitigation to a more proactive approach to improving the community health and well-being in cities.

Healthy and Age-Friendly City Action and Management Planning

This tool builds on the results of the impact assessment; prioritizes actions and investments; identifies roles and responsibilities, financial and human resource requirements; and sets a management and action plan to maximize positive health opportunities based on data from feasibility studies, scoping activities, baseline information, business cases, and strategic frameworks.

It follows three steps. The first involves ranking risks and evaluating the list of health risk mitigation options in close collaboration and consultation with city leaders, stakeholders, and communities. The projects are prioritized based on technical feasibility, social responsiveness, and financial and economic viability. The second step covers the preparation, financing, and implementation of health management plans, which will be the blueprint for improving the urban environment. The last step involves monitoring and evaluation, which includes regular surveys on health improvements, healthy city profile updates, cost and benefit assessment, and identification of gaps in operation or design.

Hierarchy of Needs

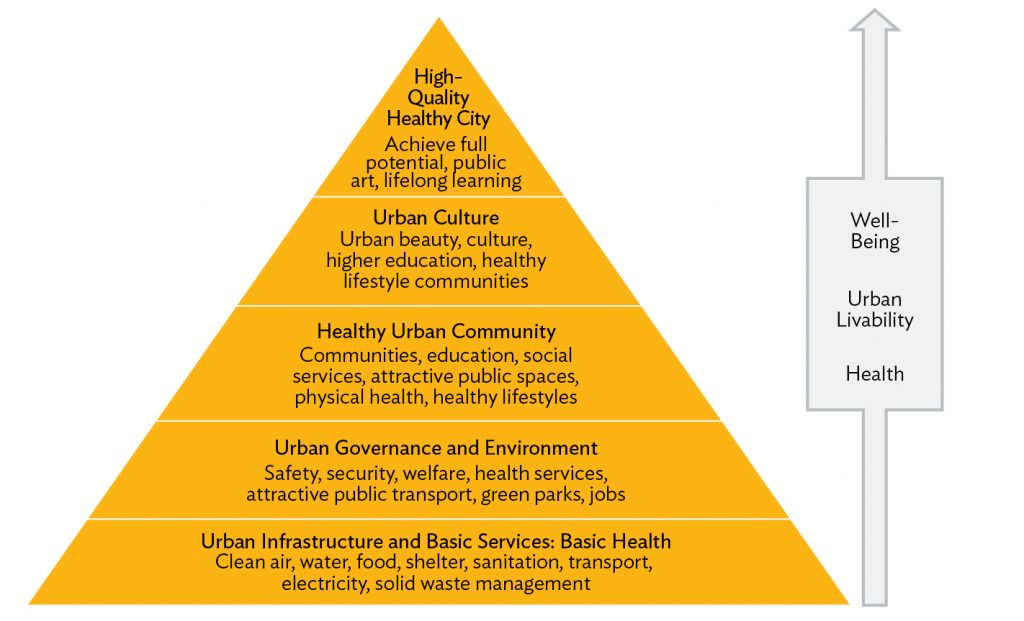

The basic concept behind these tools is that public health needs and objectives in cities follow the hierarchy of needs principle:

Based on a modified version of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs framework, the basic urban structure at the bottom requires clean air, water, and shelter as basic services. At the top is a High-Quality Healthy City that enables residents to achieve their fullest potential through services and facilities that enhance well-being, urban livability, and health. This is achieved through a holistic and integrated approach to urban planning and management and involves the active participation of stakeholders.

Figure 1: A Framework for Attaining a Healthy and Age-Friendly City

Using the hierarchy of needs as a roadmap, the impact assessment addresses the needs and challenges of specific age groups while the planning tool prioritizes projects and investments based on data. Plans for financing, implementation plan, and monitoring are developed in this iterative approach. The two-stage framework primarily aims to provide a structured and practical guide to assess health and aging needs, challenges, impacts, and opportunities of existing urban areas and of new urban developments. This will help make health and age-friendly city planning easier.

As shown in the process diagram below, the left side is for urban rehabilitation and retrofitting existing cities and urban areas while the right side is for urban master plans and new projects. Residents, communities, and stakeholders are engaged throughout the whole process. By linking the impact assessment with the planning tool, a financing and implementation plan of priority actions based on consultations is produced, and then monitored and evaluated.

Figure 2: Healthy and Age-Friendly Cities Multidisciplinary and Participatory Process

Here is a step-by-step example of how the framework may be used for existing urban areas:

Implementation in the People’s Republic of China

The PRC launched in October 2016 a program that calls for a “health in all” policies approach to help prevent and treat diseases and promote healthy lifestyles. A practical and flexible framework can help implement the health-focused program in cities and prioritize the health and aging experiences and outcomes of urban residents.

ADB has applied the framework to two projects in the PRC. The first one was for the Yunnan Lincang Border Economic Cooperation Zone Development Project. Based on the results of the rapid Health Impact Assessment, recommendations were made to address several health issues that included the risk of communicable disease transmission, demand for local health services, and road safety. Next, a public health management plan was initiated under this project not only to mitigate the infectious disease risk but also improve to the overall health and well-being of the people.

The second project is the Jilin Yanji Low-Carbon Climate-Resilient Healthy City Project. Located in Yanji city, the project focused on improving urban livability of the medium-sized city through the integration of public transport, non-motorized transport, and green spaces, and improvement of the water supply and wastewater management systems. A baseline assessment of health determinants and risks and adverse impacts of the project was conducted, and it identified challenges and opportunities for improved health outcomes. Meanwhile, the project will implement a Healthy and Age-Friendly City Action and Management Plan that will focus on controlling communicable diseases, significantly reducing non-communicable diseases, promoting healthy lifestyles through health care services, and establishing urban and building design features that provide access to people of all ages.

The initial target of the framework was the PRC, but it can also provide guidance to other countries. It is relevant for cities at all development stages, especially in view of the COVID-19 pandemic and demographic trends.

ADB. 2018. ADB Loan Supports Cross-Border Trade, Urban Services in Yunnan, PRC.

ADB. 2018. A Health Impact Assessment Framework for Special Economic Zones in the Greater Mekong Subregion. Manila.

ADB. 2018. Health Impact Assessment: A Good Practice Sourcebook. Manila.

ADB. Jilin Yanji Low-Carbon Climate-Resilient Healthy City Project.

ADB. Yunnan Lincang Border Economic Cooperation Zone Development Project.

N. Habib, S. Rau and S. Roth. 2020. Healthy and Age-Friendly Cities in the People’s Republic of China. Webinar. 14 May.

N. Habib, S. Rau, S. Roth, F. Silva, and J. Shandro. 2020. Healthy and Age-Friendly Cities in the People’s Republic of China: Proposal for Health Impact Assessment and Healthy and Age-Friendly City Action and Management Planning. ADB East Asia Working Paper Series. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

World Health Organization. 1985. Promoting Health in the Urban Context. WHO Healthy Cities Project.

WHO. 2007. Global Age-friendly Cities: A Guide. France.

Health Specialist, East Asia Department, ADB

Senior Urban Development Specialist, East Asia Regional Department, ADB

Principal Knowledge Sharing and Services Specialist, Sustainable Development & Climate Change Department, ADB

This blog is reproduced from Development Asia.

© 2025 Regional Knowledge Sharing Initiative. The views expressed on this website are those of the authors and presenters and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), its Board of Governors, or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data in any documents and materials posted on this website and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in any documents posted on this website, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area.