Rainbow community, Huiji district, Zhengzhou city, Henan province

In the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the community is the critical battlefield for preventing and controlling the coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Early detection, early reporting, and reduction of transmission risk are the community’s weapons. Community engagement is key to “turning off the tap” of COVID-19. Rainbow, a community of 5,655 households, embodied these good practices.

On 24 January 2020, the eve of Chinese New Year, millions were on the road rushing to family reunions. That was when the news broke: a lot of COVID-19 cases had been found in Wuhan and the city was locked down from the evening of 23 January 2020. Rainbow’s New Year preparations came to a halt, and the fight against the pandemic started and has continued since then.

Community mobilization

“Protect neighborhoods for our communities, protect communities for our city.” ~ Community branch secretary

Rainbow’s leadership immediately mobilized residents into joint working groups and set up a data platform and a health communication network. “We declared war on COVID-19,” said the community branch secretary. “Our duty is to control it.”

Strengthening community leadership and organization

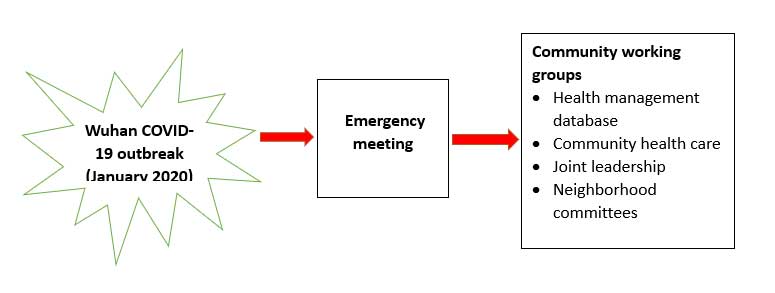

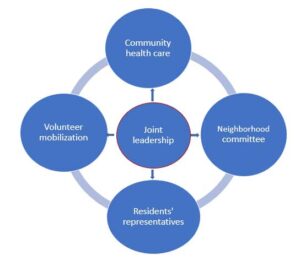

Community leaders called emergency meetings. They formed a joint prevention and control leadership working group, with representatives from the community committee, health sector, grid team, and residents. They set up a communication and information exchange mechanism among local organizations and formed working groups for the neighborhood committee, health care, volunteers, and residents (Figure 1).

Building community information database

The joint team built an information database to understand residents’ baseline conditions. Committee members conducted a diagnosis and needs assessment in the first 2 weeks. Community workers went door to door to survey households. They screened those who had returned from Wuhan and other high-risk areas. They collected households’ health management information, including personal information, work settings, travel history, and so on, and stored it in the database to guide the groups’ work.

Public health education and health promotion

Committee members launched health information and education drives. Mobile loudspeakers made the rounds to remind people to wear face masks, wash their hands, practice social distancing, ensure their rooms’ natural ventilation, observe cough etiquette, among others. Health workers put up more than 3,000 posters containing key health messages in neighborhoods and handed out brochures about how residents could protect themselves.

The residents’ representatives were key. They compiled residents’ concerns and inquiries for public opinion monitoring, which shaped key messages and information. They documented rumors and misinformation so that community health workers could counter them with the help of health education professionals. The residents’ representatives closely followed official social media accounts and forwarded the latest information, announcements, and knowledge to everyone in their social media networks.

Community participation and involvement

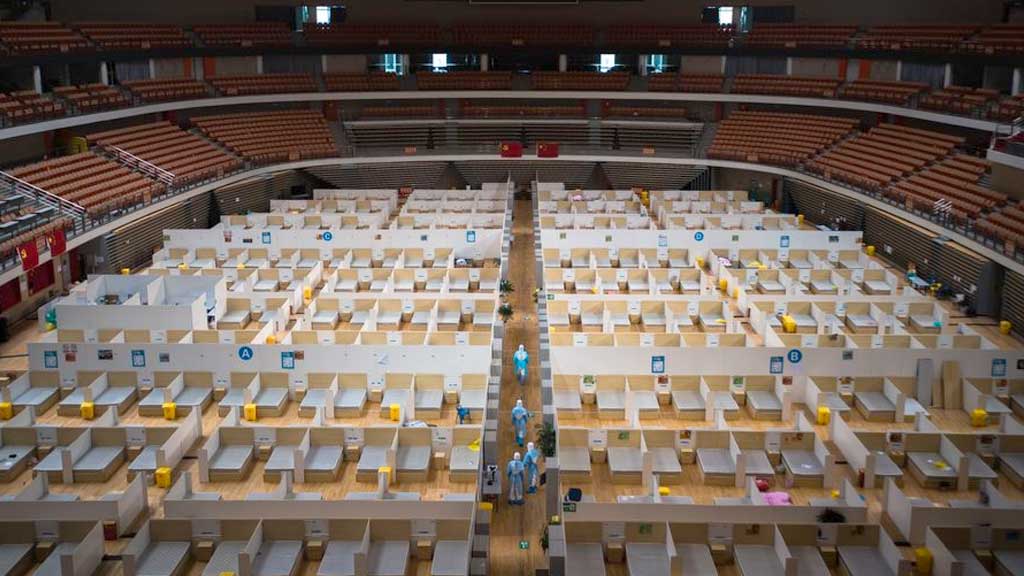

The residents were the backbone of COVID-19 prevention and control (Figure 2).

Management workers of residential buildings (i) sent out epidemic notifications, government policies, and updates via residents’ networks and WeChat groups; (ii) called on everyone to take action and do their share by not traveling, for example, or gathering or going out; and (iii) quickly notified the health-care working group of high-risk people arriving from abroad or high-risk areas.

Community singing and dance groups shared health education information with their members every day. “Everyone’s more aware of how to prevent and control COVID-19,” Yi Wang, the community dance team leader, said proudly. “They stay home, easing the checkpoint personnel’s work.”

The 1-2-3-4 model for managing home quarantine

Rainbow strictly implemented the 1-2-3-4 model to manage home quarantine. With the virus spreading and more people returning from Wuhan and other high-risk areas, home quarantine was an important deterrent against COVID-19. Rainbow recruited volunteers for the Little Red Elephant team to bring support services to quarantined people 24/7.

The 1-2-3-4 model was carried out as follows:

- Community grid team members inspected quarantined households every day to ensure people did not go out. Team members asked questions such as, “Did anyone of you travel for the Spring Festival or other reason? Does anyone here have flu symptoms?” They also instructed household members to monitor their body temperature.

- Community health workers were responsible for two things: (i) visiting people’s homes to monitor the body temperature and symptoms of those in quarantine and (ii) providing them with psychological counseling and teaching them to protect themselves and disinfect their homes.

- Community volunteers collected household garbage every day for centralized disinfection.

- Community volunteers delivered vegetables and other necessities to those in quarantine, shopped for them, and gave them packs containing a thermometer, a face mask, a registration form, disinfectant, and health education materials. All goods ordered by those in isolation were delivered to the entrance of the neighborhood. Then community workers and volunteers instructed residents to get them in batches according to a schedule, avoiding direct contact with anyone and maintaining social distance. Community workers and volunteers also helped patients with chronic diseases buy medicine or visit hospitals for check-ups.

Menglan Zhang, a resident, was grateful to the community workers and volunteers. “When I ran out of food, they brought me food. When I needed something, I called them and they shopped for me. They even sent us yuanxiao (glutinous-rice balls) for the Lantern Festival even though we didn’t ask for them.”

Author

Xuefeng Zhong

Public Health Specialist (Consultant)