Building the Climate Change Resilience of Mongolia’s Blue Pearl: The Case Study of Khuvsgul Lake National Park

Ecosystem-based adaptation solutions can reduce vulnerability and build resilience of urban areas to climate change.

Introduction

Redeveloping urban areas through climate adaptation measures can make cities more resilient to the hazards of extreme weather and better cope with water surplus or shortage, heat stress, and land subsidence. Moreover, implementing such measures can result in co-benefits for public health, biodiversity and social well-being.

Cities are designed according to current or past conditions. Land-use changes because of continuous population growth. Urbanization can lead to reduced infiltration, increased runoff and water demand, and urban heat island effect. This urbanization leads to reduced infiltration, increased runoff and water demand, and urban heat island effect. Climate change can also magnify existing risks and vulnerabilities of urban areas to flooding, drought, and extreme heat.

Soil and vegetation naturally absorb 90% of rainfall through infiltration into the ground and evaporation into the air, while hard city surfaces like asphalt, pavement, and roofs rapidly shed water, creating huge volumes of fast-flowing runoff. Developed areas create over 500% more runoff than natural areas of the same size.

Ecosystem-based (or nature-based) solutions have been developed over the past decades in response to the growing need to improve urban resilience as well as environmental sustainability. Digital tools, such as the Climate Resilient City Tool, are available to help urban planners evaluate climate risks and promote collaboration of stakeholders for ecosystem-based adaptation measures.

What is ecosystem-based adaptation?

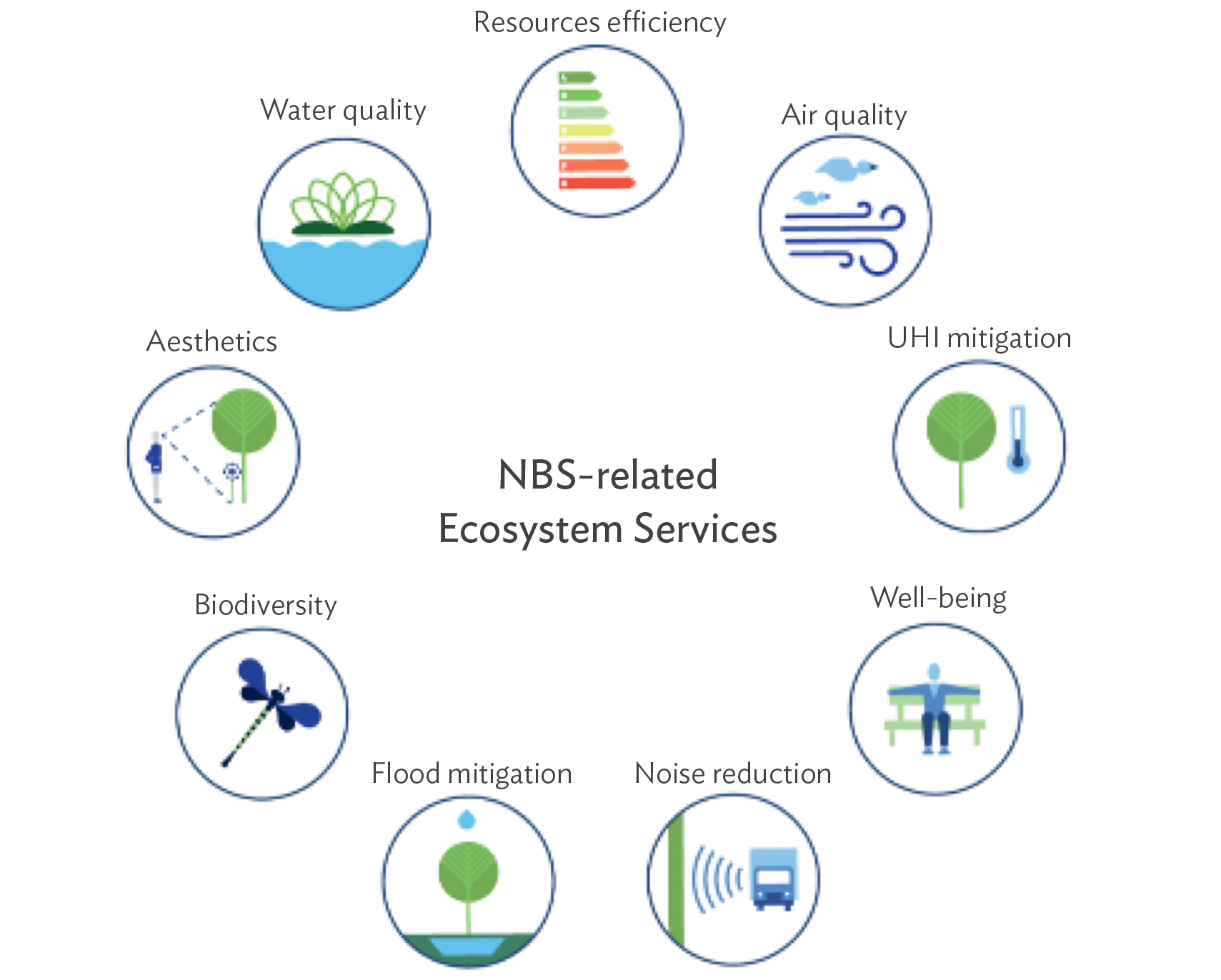

Inspired and supported by nature, ecosystem-based adaptation measures are cost-effective solutions that harness ecosystem services to reduce vulnerability and increase the resilience of cities to extreme rainfall, drought and heat–aggravated by climate change. Ecosystem-based adaptation measures follow the basic principles of conservation, sustainable management, and restoration of ecosystems. These include soft and hard engineering measures to develop green or hybrid (green–blue–grey) solutions that integrate plants, water systems, and green infrastructure. They provide environmental, social, and economic co-benefits and help people adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Figure 1: Ecosystem Services of Nature-Based Solutions

Measures that promote ecosystem-based adaptation improve a city’s climate resilience by enhancing infiltration and evapotranspiration,2 and capturing and reusing stormwater. The goal is to restore a city’s capacity to harvest, absorb, infiltrate, purify, store, use, drain, and manage rainwater. They mitigate the water discharge from heavy rainfall, retain and degrade pollutants, reduce the amount of stress on a city’s wastewater treatment facilities, and help maintain the natural water cycle. Examples of these measures include green roofs, porous pavements, raingardens, bioswales, rainwater tanks, smart irrigation, and urban forest. (See the examples of 43 ecosystem-based adaptation measures.)

Environmental, social, and economic co-benefits derived from ecosystem-based adaptation measures include:

Apart from improving the city’s livability and creating a healthier and more attractive city, ecosystem-based adaptation activities can further contribute to the sustainable use of energy and urban resources while enhancing the urban ecosystem and biodiversity. Through urban regeneration, they can help revitalize neglected areas and increase land value and government revenues. Recreational spaces that use ecosystem-based adaptation measures improve people’s well-being and create tourism services, that in turn, can create jobs and stimulate local economies.

What is the Climate Resilient City Tool?

Urban climate resilience planning involves multiple participants. Planning, implementation, and maintenance of ecosystem-based adaptation measures require the cooperation of city bureaus and departments, each with the need to adapt their policies, procedures, regulations, and practices.

In order to support cities in climate resilience planning and design, there are science-based tools available for hazard exposure and vulnerability analysis. Some tools present an overview of potential solutions and/or best practices to mitigate the risks. One of these tools is the Climate Resilient City Tool, an information and technology-based urban resilience and adaptation planning support tool that was developed by Deltares to assess climate risks, identify key flood-prone areas, and support collaborative spatial planning of ecosystem-based adaptation measures. The web-based tool can be accessed using a touchscreen device for collaborative design planning or a single personal computer to individually explore adaptation options.

The Climate Resilient City Tool provides an initial quantitative estimate of the resilience capacity improvement, co-benefits, and associated costs of the proposed adaptation measures. This will allow design participants to collaboratively explore alternative choices and come up with an initial concept. The initial design can then be used as input for a more detailed design of the landscape and drainage plan of the project area.

It facilitates dialogue among stakeholders to identify priority areas for climate resilience improvement. Policymakers, government authorities, planners, designers, and practitioners can work together to determine the requirements of the priority areas and set the adaptation targets. It is a user-friendly way to practice collaborative city development planning that allows representatives from various bureaus and organizations to discuss multi-disciplinary concerns, co-create adaptation scenarios, and co-design a conceptual plan of a resilient and attractive blue-green infrastructure for a community. With detailed information provided for 43 ecosystem-based measures, design participants can select specific interventions that can be implemented at the street or block level.

Ecosystem-based Adaptation Measures in an ADB Project

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) supported the preparation of a localized version of the Climate Resilient City Tool for the city of Xiangtan in Hunan Province, People’s Republic of China. Information on the effectiveness and costs of ecosystem-based adaptation measures have been adjusted for local conditions.

Xiangtan is an old industrial city undergoing rapid urbanization and industrial transformation. Some areas have been experienced flooding because of increased rainfall and drainage capacity has been exceeded. The Climate Resilient City Tool, developed in English and Chinese, was used in the project preparation of the urban climate resilience component of the Xiangtan Low Carbon Transformation Sector Development Program. A flood hazard map was generated for Xiangtan based on an analysis of local conditions.

Climate resilience experts trained local government authorities and other stakeholders on urban hazards and challenges, urban climate resilience, adaptation planning, and nature-based solutions, including ecosystem-based adaptation measures. In the design workshop, participants used the Climate Resilient City Tool to prepare a concept design for two project areas.

A new hospital to be constructed in Xiangtan is located in a critical flood-prone zone and requires more than 5,000 cubic meters of retention, detention, and storage capacity for pluvial flood protection. The concept design considered several ecosystem-based adaptation measures, including rainwater gardens, systems for rainwater harvesting, catch pits, permeable pavement, urban wetlands, and green roofs. These measures aim to create large peak storage volumes for drought resistance and flood protection, as well as improve runoff water quality and enhance green spaces.

Initiatives to be implemented on and along one of the main roads involve converting trees to tree pits, creating rain gardens for treating stormwater from the side pathways, modifying or relocating catch pits to new rain garden areas, creating porous pavement for cycle lanes and pedestrian walkways, and developing subsurface infiltration for water storage under cycle lanes and pedestrian walkways. These will improve infiltration, reduce runoff pollution, decrease drainage and peak volumes of stormwater, and improve the landscape and street aesthetics. These will help strengthen biodiversity and support Xiangtan’s transition into a “sponge city.”3

Conclusion

Ecosystem-based adaptation measures are among the most effective ways of advancing climate resilience by integrating the use of biodiversity and ecosystem services while maximizing co-benefits.

Collaborative city development planning is needed to discuss multi-disciplinary concerns and co-create conceptual plans for a resilient and attractive city.

Applications of the Climate Resilient City Tool in various settings and contexts in several cities have illustrated the added value of the toolbox in bringing policy and practice together with the help of science for a more water-robust and climate-resilient urban environment.

ADB. 2020. $200 Million in ADB Loans to Demonstrate a Low-Carbon and Resilient City Growth Model in Xiangtan, PRC. News Release. 13 October.

ADB. China, People’s Republic of: Xiangtan Low-Carbon Transformation Sector Development Program.

Deltares. Climate Resilient Cities Toolbox.

Deltares. Ecosystem-based Adaptation Measures Available in the Xiangtan Climate Resilient City Toolbox.

Senior Urban Development Specialist, South Asia Department, ADB

Team Leader, Urban Land & Water Management, Deltares

Urban Water Management Specialist, Deltares

This blog is reproduced from Development Asia.

It is time to establish partnerships and expand to a whole-of-society approach to cope with the disasters and crises that are increasingly threatening developing countries.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought unprecedented disruptions to the world. The disease itself and the containing measures brought societies and many public services to an abrupt halt.

Flood risk management is, without exception, affected by such disruptions. Infrastructure development, planning and coordination, monitoring, and capacity building activities are all suspended. The public sector, on which flood risk management heavily relies, has been forced to redirect attention and resources to manage the pandemic, where they are needed most immediately.

But floods do not wait for the virus to go away. The 2020 flooding season in the People’s Republic of China has arrived earlier than usual, just as the country reemerged from an unprecedented large-scale lockdown. By mid-August 2020, flooding had affected 63.5 million people, with direct economic losses standing at $25.9 billion. The floods also claimed 219 lives and displaced 4 million people through emergency evacuations.

In large parts of Bangladesh and India, record setting rainfalls have caused rivers to swell to dangerous levels, claiming more than 1,000 lives and displacing millions. Government officials have struggled to provide temporary shelters while maintaining social distancing. Other emergency relief organizations find themselves unable to reach out and deliver life-saving essential supplies due to many COVID-19 related restrictions.

During difficult circumstances such as this, people find innovative solutions by working together.

In Chongqing, a mega city located along the Yangtze River in the People’s Republic of China, flood managers and public health officials are for the first time working together on environment and pandemic management. They originally planned to build a flood and pollution risk management system, in what was a pilot effort to put together different environment problems, and find common solutions using shared resources and expertise. The system also aimed to get people to work together early on before the problems happen.

With the outbreak of COVID-19, the managers quickly expanded the system to include responses to the public health emergency. The original multi-agency flood and pollution response and communication system was modified to accommodate the needs of public health management.

These changes include establishing working relations between flood and health managers, expanding environmental monitoring to cover not only extreme weather conditions, floods, and pollutants from industry, but also waste water from healthcare facilities and isolation centers. Smart infrastructure such as multi-function emergency shelters are reconfigured with portable medical equipment to accommodate flood and acute pollution evacuees as well as infectious disease patients. The changes turned the environment management facilities and systems into extensions of health facilities which allowed non-health personal and infrastructure to support large scale emergency responses.

During difficult circumstances such as this, people find innovative solutions by working together.

This type of collaboration can be useful in countries prone to frequent natural and manmade disasters, where disease and environment monitoring is weak, financial resources are tight, and institutional coordination needs strengthening.

Countries can plan for emergency situations caused by large scale disasters and health emergencies. Such planning includes public awareness campaign and education, environment monitoring, disaster and pandemic early warning, multi-agency coordination and mobilization of citizens and resources.

We can break silos and work together to prepare for many types of public emergencies. These include natural disasters such as floods, earthquakes, typhoons, and wildfires, many of which are getting worse with the effects of climate change; human induced environment disasters such as acute pollution; and sudden outbreaks of infectious diseases. After all, there is already much expertise and many resources existing in different sectors such as environment, urban management, agriculture, forestry, telecommunications, transportation, and health.

By working together, we can mobilize more resources from different sectors into a common pool to respond to various emergencies. This way there is more available emergency response expertise and personnel, more information and public communication channels, and more infrastructure and equipment. A common pool also helps to make resource use more efficient. It may be rare for any of the above-mentioned crises to happen. But when they do, they put immense pressure on the resources available to individual departments.

There are already good examples. Sports complexes, schools, and city halls are often used as emergency shelters for typhon or earthquake evacuees, and as temporary COVID-19 isolation facilities. These examples show that natural and environment management facilities can help strengthen public health management, which in turn improves medical care for injured evacuees should such events happen.

To maximize such benefits a coordinated approach is required, and several dimensions should be considered, including high-level planning and response mechanisms that bring together departments and agencies; coordinating and working across sectors, or areas of expertise; information sharing and technical know-how among groups that do not usually work together; sharing infrastructure, equipment, and other facilities to keep costs down and support those areas most in need; increasing public awareness and training for emergency response.

With new waves of infections observed in many countries, the pandemic is unlikely to disappear anytime soon, putting prolonged pressure on limited social, financial, and technical resources. It is time to break sectoral silos, establish “unlikely” partnerships, and expand to a whole-of-society approach to cope with the many disasters and crises that are increasingly threatening development outcomes.

Water Resources Specialist, East Asia Department, ADB

Senior Water Resources Specialist, East Asia Department, ADB

‘Build back better’ is often easier said than done after a disaster, but one example from the People’s Republic of China shows that it can be done well.

Build back better refers to largely aspirational plans to achieve recovery from disasters that is not only complete but leads to improvements above and beyond the pre-disaster status quo. Build back better is often so vaguely defined that policymakers and analysts can declare their aspiration to build back better as fulfilled, even if the long-term outcome is less than successful. Indeed, the positive evidence for build back better is quite thin, but one notable success story is the Wenchuan earthquake recovery. As documented in our 2009 study, the key to the successful recovery was the massively generous and exceptionally speedy assistance of the People’s Republic of China central government and its unaffected provincial governments.

On May 12, 2008, a massive earthquake measuring 8.0 on the Richter scale struck the southwest area of the People’s Republic of China, followed by a large number of aftershocks. The epicenter was in Wenchuan County, 92 kilometers northwest of the Sichuan provincial capital of Chengdu. The disaster affected 10 provinces and cities, with Sichuan suffering by far most of the damage, including 99% of mortality and morbidity. The most severely affected areas in Sichuan were mountainous, mostly at 3,000 meters above sea level, and economically less-developed and impoverished. But some more developed urban regions such as Chengdu, Deyang and Mianyang were also hit. The earthquake left more than 87,000 people dead or missing, nearly 375,000 injured, and many more displaced.

The earthquake badly damaged or destroyed houses, property, rail transport, power supply, water and sanitation facilities, hospitals and clinics, roads, buildings, and communication networks throughout the affected region. The total reconstruction cost was estimated at RMB 1 trillion, nearly equal to the gross domestic product of Sichuan Province or 3.9% of the national GDP in 2007. The vast majority of households and businesses were not covered by insurance, as is typical for disasters in low- and middle-income countries.

In the People’s Republic of China, the central government took a lead role in rehabilitating Wenchuan after the 2008 earthquake.

In 2009, in response to the global economic crisis and the Wenchuan earthquake, the government passed a massive 4 trillion RMB stimulus package, of which 25% went to earthquake reconstruction. In addition, richer provinces were paired with disaster-affected counties under a fiscal solidarity scheme and were required to put aside 1% of provincial government revenues to assist in the reconstruction work in partner counties. Altogether, those funds far exceeded the ordinary budgets of the earthquake-damaged counties. In addition, by the end of September 2009, 79.7 billion RMB in social contributions had been mobilized from individuals and NGOs inside and outside of the People’s Republic of China.

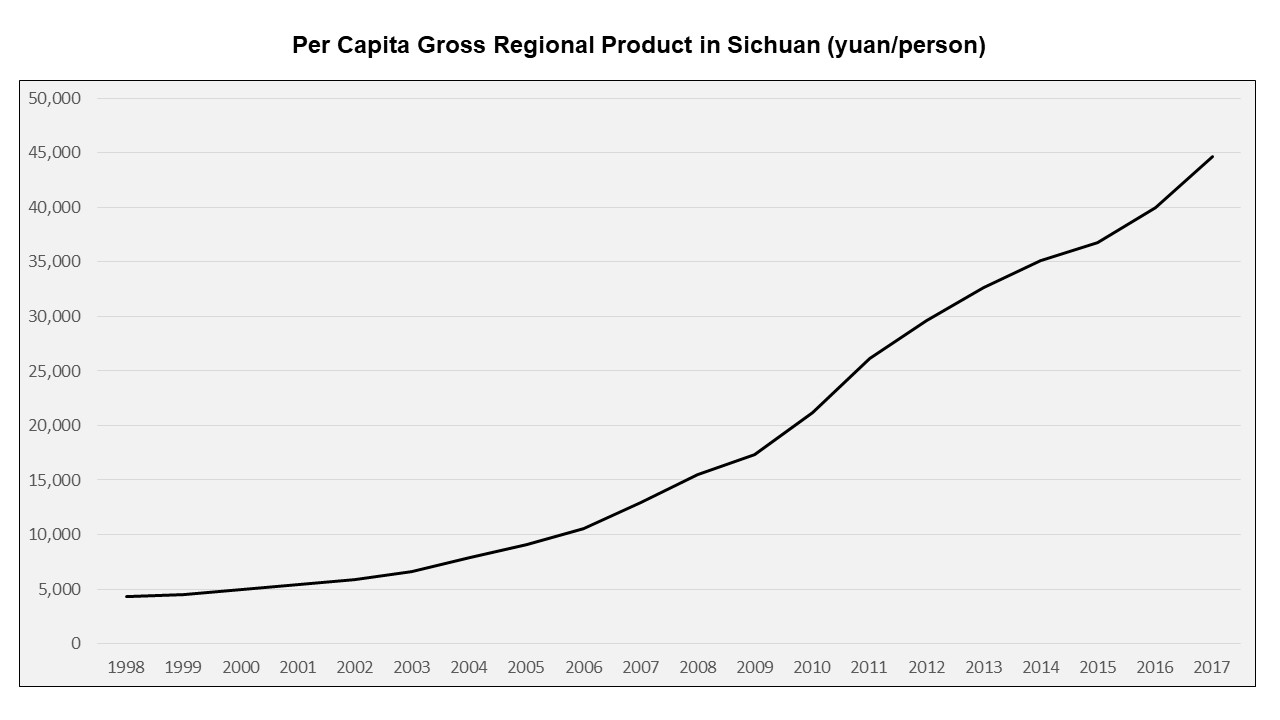

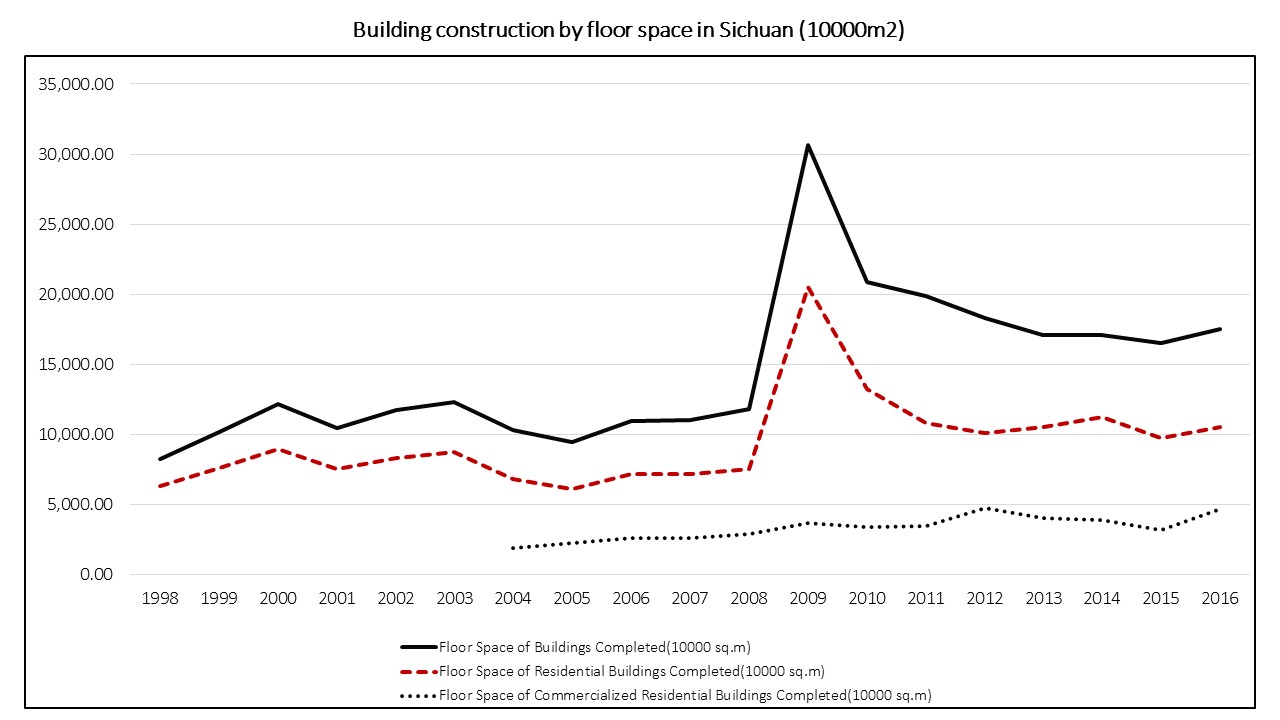

As a result of massive reconstruction spending, per capita GDP in Sichuan province did not change noticeably during and after the 2008 earthquake except for a marginal reduction of growth in 2008, the year of the earthquake and also of the global financial crisis. A major driver of the quick macroeconomic rebound was the construction sector, which increased rapidly since 2008 and remains strong even years after the reconstruction boom of the immediate post-earthquake period.

Further analysis, using data from a survey conducted among 3,000 rural households ten months after the earthquake, finds that asset and income losses of households were substantial, especially in the hardest hit areas. However, government subsidies for affected households in 2008 were so large that mean income per capita was 17.5% higher in 2008 than in 2007, and the poverty rate actually plummeted from 34% to 19%! Analyzing detailed information on household income from various sources, the survey indeed concluded that households on average were better off after the earthquake.

The four basic criteria for assessing the effectiveness of any build back better effort are safety, speed, inclusiveness, and long-term economic potential. Evidence suggest that the Wenchuan earthquake recovery scores especially high on speed and inclusiveness, and most likely safeguarded the long-term economic potential of the earthquake area. Above all, Wenchuan highlights the indispensable role of a concerted and decisive government recovery effort backed by massive resources for successful build back better. Such generous resourcing, which is the exception rather than the norm, can empower communities to cope with and bounce back from even the most catastrophic disasters.

This article is based on the findings of the ADB report ‘Asian Development Outlook 2019: Strengthening Disaster Resilience.’

Professor of Economics, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Principal Economist, Economic Research and Regional Cooperation Department, ADB

Principal Economist, Economic Research and Regional Cooperation Department, ADB

This blog is reproduced from Asian Development Blog.

© 2026 Regional Knowledge Sharing Initiative. The views expressed on this website are those of the authors and presenters and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), its Board of Governors, or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data in any documents and materials posted on this website and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in any documents posted on this website, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area.