The UN’s new initiative presents a promising framework to make agriculture and food systems more sustainable and resilient

Agriculture and food systems are profoundly vulnerable to climate change. Severe droughts and floods, changes in rainfall patterns, and other climatic impacts affect agriculture more than any other sector. Asia and the Pacific, in fact, will be the region most affected by worsening climate impacts; recent events include record-breaking droughts in the Yangtze River basin, which resulted in an estimated $5 billion worth of damage while affecting countless lives.

At the same time, globally, agriculture and food contribute to more than one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to a 2019 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change special report on climate change and sustainable land management. This makes food and agriculture critical as both a vulnerable sector heavily affected by climate change and a significant contributor to climate change.

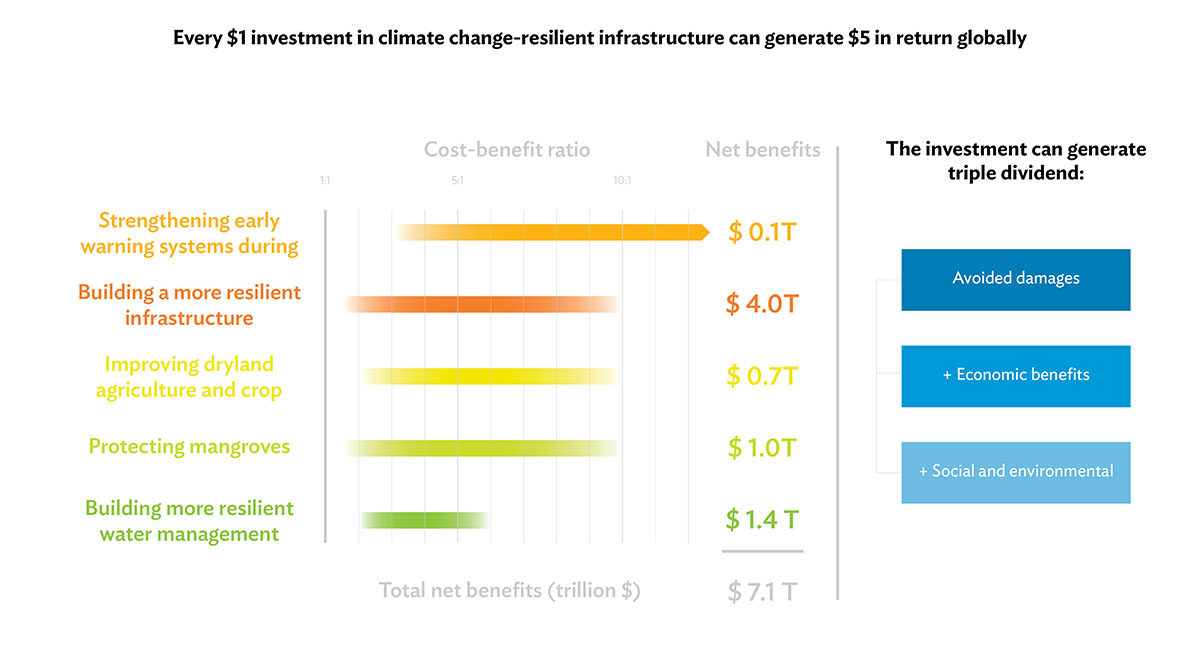

Agriculture and food systems also offer meaningful opportunities to address climate change. One is to achieve more sustainable food security by strengthening the system’s resilience and investing in inclusive adaptation to climate change. Another is to mitigate climate change through emissions reduction and carbon sequestration.

Both these opportunities can be achieved by promoting sustainable agricultural and food systems, and engaging key stakeholder groups, including women — a larger percentage of whom depend on agriculture for their livelihood. This is particularly important in developing countries, which face significant food security challenges. Such a sustainable transformation will significantly contribute to the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals while helping maintain the 1.5 C ambition to limit climate change impacts.

Encouragingly, in November 2022, the presidency of the 27th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 27) launched the Food and Agriculture for Sustainable Transformation Initiative (FAST), which is aimed at directing climate resources, particularly finance, to develop more sustainable agriculture and food systems. It will focus on three pillars: finance, knowledge and capacity, and policy. A detailed implementation plan is being finalized, but several critical components are essential to help achieve success.

First, the FAST must promote effective coordination among development partners to identify gaps and avoid duplication of work. The FAST will be facilitated by the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization and will require active and effective participation by other agencies. Earlier, the Asian Development Bank announced plans to deliver more than $14 billion from 2022 through 2025 to support food security, including through strengthening food systems against climate change and preventing biodiversity loss.

Other organizations are on the same track. The World Bank has made agriculture and food priorities in its first climate change action plan, aiming to leverage more resources for sustainable agriculture. Development partners will need to work together under the FAST framework for meaningful impacts in the developing world.

Second, the FAST must support enabling environments, including policy incentives and governance that promote inclusive, climate-positive change in food systems. Policies and institutions at the local, national, and international levels need to incentivize the development and adoption of new technologies and practices and ensure adequate finance, including private sector investments. Governments or inter-governmental agencies should take the leading role in establishing sound policies and incentives, and ensuring effective implementation.

Third, the FAST should support stakeholders along the value chain, from production, processing, and storage to trading and consumption, to improve their resilience to climate change. For example, higher temperatures and humidity lower on-farm productivity as weeds and disease increase the risk of post-harvest losses, particularly for traders and aggregators who deliver in bulk to processors. Climate adaptation can be strengthened through storage technologies such as cold chain and improved drying techniques.

Fourth, the FAST must promote promising innovations to support adaptation and build resilience while increasing productivity. New crop varieties can better withstand climate shocks and improve yields. Solar energy can be used for irrigation, storage, transportation, and processing. Digital technology can expand access to farming knowledge and services allowing farmers to adapt practices to local conditions and improve market access and profitability.

Climate-smart practices, such as no-till farming, bio-waste management, agro-forestry, and landscape management, will also support mitigation by sequestering carbon and reducing GHG emissions. Automatically controlled drip irrigation combined with dynamic soil testing can improve system resilience to extreme droughts.

The FAST should also campaign for responsible consumer behavior to minimize individual’s ecological or carbon footprint, especially in advanced countries. Reducing consumption of processed food and red meats, as well as food waste can significantly reduce emissions.

Finally, and most importantly, the FAST must focus on farmers, as they are the primary agents for sustainable transformation on the ground and are most vulnerable to climate change, especially women, who represent approximately 43 percent of the agricultural labor force globally (47.5 percent in the PRC). Critically, women farmers show greater sensitivity toward environmental activities and are more involved with sustainable agriculture practices. They must be equipped with sufficient knowledge, technologies, and incentives to make transformation happen.

The FAST presents a promising framework to make our agriculture and food systems much more sustainable and resilient to climate change, and to reduce carbon emissions. Its success depends on a comprehensive, inclusive, and integrated approach that considers all stakeholders along the value chain.